When I began work as The American Scholar’s books editor a decade ago, I inherited a few things: an unopened pack of floppy disks from the early 1980s, a drawer full of ancient files no one remembered anything about, a collection of lightly used pens and highlighters, and an elderly bibliophile named Jake.

The magazine had a smaller staff back then, and there were days when I was the only one in the office. On one such day, Jake walked in and introduced himself. He looked as if he had materialized out of a sepia-toned photograph, complete with a gray tweed suit and vest, a stiff-collared dress shirt with a bow tie, freshly shined, two-toned shoes, a fedora, and despite the warm, early fall weather, a trench coat. He told me that he had been a contributor to the Scholar for many years, particularly during the tenure of our former editor Joseph Epstein, and that he had received special dispensation (presumably at some point in the distant past) to take whatever books he wanted from our discard stacks. And with that, he got to work, amassing a tower of philosophy, history, and biography on my desk. Even after he had whittled down his selections, the pile was too heavy for him to carry, so I had them sent to his house. I thought, when he left, that I wouldn’t see him for a while—all those books would surely take months or years to read—but soon enough, he was back for more, as he would be again and again. Indeed, Jake became a regular presence in my life. He had a maddening knack for appearing in the doorway just when I was at my busiest, usually on the hectic days just before closing an issue of the magazine. But I always looked forward to his visits, which over time, grew to be less about book grabs than good conversation.

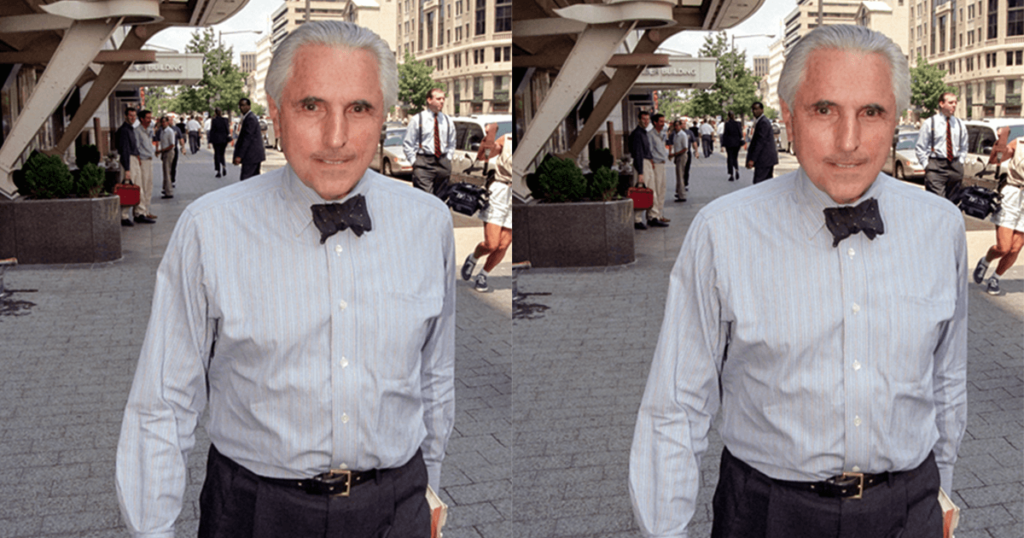

My friendship with Jake, I often thought, was of the “only in Washington” variety. The world knew him as Jacob A. Stein, an eminent attorney who had played a central role in some of Washington’s most publicized and controversial legal proceedings of the past 50 years. He was the only Watergate defense lawyer to have his client acquitted, and years later, won immunity for another client, former White House intern Monica Lewinsky, freeing her to testify against President Bill Clinton. In the intervening years, he served as independent counsel in an investigation of Reagan advisor Edwin Meese III for financial improprieties, represented former Reagan press secretary James S. Brady in litigation related to the 1981 assassination attempt on the president (during which Brady was seriously wounded), and successfully defended Oregon Senator Bob Packwood against charges of influence peddling. As Packwood later told a reporter for The Washington Post, “He’s the kind of lawyer that if you were indicted for murder, found guilty and hanged, you’d still think you had a good defense.”

But the Jake I knew wasn’t just the calculating litigator of legend; he was an insatiable reader and deep thinker who desired nothing more than to spend the day discussing ideas. He was also extraordinarily generous. At one point, we discovered we shared an admiration for the Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, which appeared in 1911—the last great trove of universal knowledge to be published before the First World War destroyed the sense of imperial certainty that reigns in its dusty volumes. Many of the entries were penned by the greatest thinkers of the time—John Muir, T. H. Huxley, Ernest Rutherford, and Algernon Charles Swinburne, to name a few—and Jake reveled in dipping into the volumes at random to see what he could find. Had I read Andrew Lang’s entry on Mythology? What about Thomas Babington Macaulay’s essay on Samuel Johnson? No, I told him, I didn’t own a print version of the Eleventh Edition, and reading it online held little appeal. This, apparently, was unacceptable to Jake, so he gifted me a complete set of 29 volumes (he owned two!), which I now have prominently displayed in my living room. On picking up the set at his house in Northwest Washington, I discovered that Jake’s generosity may have come with some prodding: his wife, tired of living amid disordered piles of books, told me she’d been after him to get rid of as many of them as he could. I was all too happy to oblige.

Jake was the rarest of breeds—a true intellectual whose love for knowledge was undiluted by ego, professional ambition, or hunger for status. One day, he pulled a chair up to my desk and began decrying what he saw as a narrowing of knowledge among new associates at his law firm. These were some of the best young legal minds in the country, he told me, people who had excelled in law school and who had had all the right internships. They’d come into his booklined office, and as a joke, he would point to a doctored black-and-white photograph on the wall, depicting Jake riding in a convertible limousine with another man. More than once, an associate had asked, “Who’s that with you in the limo?” It was Winston Churchill. For Jake, this anecdote, small in itself, exemplified something larger and far more troubling: the dumbing down of even the most elite segment of our society. For him, a classical education was the greatest thing to which a person could aspire. And despite their obvious intelligence, many of the young people he came to know were sorely lacking in the kind of general knowledge that was universal among educated people of earlier generations.

I wish I could say that I helped ease his mind on that account. But all too often, he assumed of me a level of education, a depth of reading and thinking, to which I could not lay claim. It can be embarrassing to acknowledge what you don’t know, but in my talks with Jake, I grew comfortable doing so, if only by repetition. Whether discussing white-collar criminals of the 1950s, anticommunism, musical theater, the bit players from the Watergate hearings, or the great vaudeville players he remembered from his childhood, Jake always presumed that I could follow wherever his mind chose to go. One day, for example, he came in and said that he’d been taking pleasure in reading the maxims of La Rochefoucauld, whose wisdom had come as a great comfort to him in his later years. La Rochefouwho, I asked? Jake, justifiably shocked (and I dare say, disappointed) insisted that I pick up a copy of the maxims for myself.

It was inevitable, I suppose, that Jake’s candle should burn down. During the past couple years, his visits became less frequent, although he still commandeered an astonishing quantity of books, no doubt to his wife’s continuing dismay. But Jake was visibly suffering—he still dressed like a latter-day Gatsby but had trouble focusing his mind. I could see in his eyes that he was still in there, desperate to express his thoughts and engage me in discussions of ideas and writers. But as he eventually confessed, he could no longer concentrate enough to read. The books he was still taking home had become purely aspirational—volumes he knew he would never get through.

And then he stopped coming at all. Months went by without a word from Jake, and I sensed that something was wrong, though I wouldn’t allow myself to believe the worst. One night earlier this week, thinking about him, I pulled out my copy of La Rochefoucauld maxims, one of which caused me to pause: “In the human heart one generation of passions follows another; from the ashes of one springs the spark of the next.” The next morning, I learned that Jake had died.

I will miss him dearly—and now it’s my job, our job, to carry the spark for the next generation, just as Jake carried it for us.