Too Alone in This World, Yet Not

A newly opened archive reveals further contradictions about a poet steeped in paradox

The translations of Rilke’s poetry in this essay are by Scholar senior editor Stephanie Bastek. All other translations are by the author.

The year 2025 marks the 150th birthday of the enigmatic poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and next year will be the 100th anniversary of his death at age 51. A century should be enough time to evaluate his life and literary heritage with some clarity. But it’s not. Attempts to assemble a coherent story always seem to bring contradictions to light. Rilke is universally acknowledged to be one of the supreme writers in German, yet the Prague native was deeply conflicted about Germanic language and culture, and alternately showed preferences for French, Italian, Russian, Czech, and Danish. One language that did not hold any attraction for him at all was English, but he is revered in the English-speaking world for reasons that are not entirely clear. Even the finest English translations miss the nuances of his German. Until this year, however, some of the best biographies of Rilke appeared in English, not German—Princeton’s Ralph Freedman wrote one of the most reliable and readable in 1996. But it’s not only ivory tower academics who appreciate the esoteric work of this dead poet. Lady Gaga has a line from Rilke tattooed on the inside of her left arm, next to her heart. The tragicomic 2019 film Jojo Rabbit, which won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, concludes with a quote from Rilke. And even more puzzling: The book-review website Goodreads.com clocks nearly 200,000 ratings for his work with an average approval of 4.24 stars out of a possible five. Shakespeare gets only 3.86. Just what is going on here?

Meticulous German scholars have amassed some excellent tools for exploring this question. In 1975, Ingeborg Schnack compiled a detailed chronology of Rilke’s life, a work expanded by Renate Scharfenberg in 2009 to 1,251 pages. Then in 2022, the Swiss publisher Nimbus issued three volumes, edited by Curdin Ebneter and Erich Unglaub, of about 800 firsthand accounts of Rilke left by his friends, lovers, and acquaintances. Since these recollections can be gossipy, and memory imprecise, the editors gently correct obvious errors in the footnotes. These weighty volumes mark the pinnacle of primary-source materials on Rilke’s life. But the more details that accumulate, the more mysterious his story becomes.

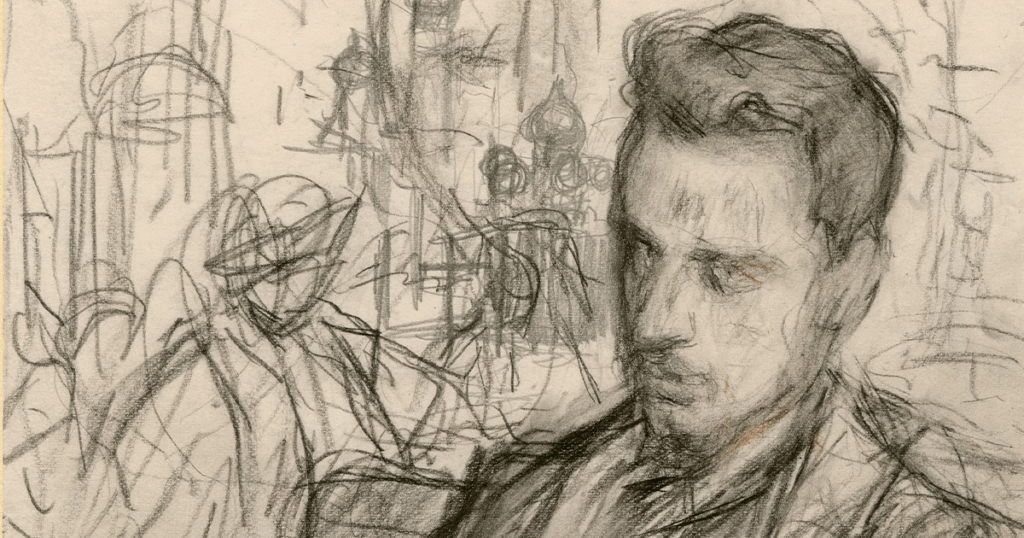

Rilke was a college dropout who scaled the heights of rather jealously guarded German literary fame. His work is considered to be at the forefront of “modern”—that is, 20th-century—writing, but he had a strong preference for reading and composing by flickering candlelight. He wrote his final masterpieces in a medieval stone tower in the Swiss Alps, provided for him by supporters, that lacked electricity and modern plumbing. He was basically unemployed, homeless, and chronically short of funds his entire wandering adult life, yet somehow he enjoyed extended stays in fabulously luxurious castles and resorts. He had bouts of intense shyness in which he avoided serious emotional commitments, but his circle of devoted friends was vast. He wrote something on the order of 17,000 letters and received an equivalent number from friends. His political views are also puzzling. He had aristocratic pretensions, but he was sympathetic to the Russian Revolution and supported communist revolutionaries in Munich at the end of World War I. And another mystery: Contemporary accounts and photographs make clear that he was awkward and homely, but he enjoyed a lifelong series of glamorous romantic relationships.

These incongruities were evident from the beginning of his writing career, when he was a teenager in Prague just before the turn of the 20th century. One compatriot, Hugo Steiner-Prag, wrote, “We lived in the same city with him, near and far at the same time. We would see him walking along the old narrow streets, dressed in black with an old-fashioned cravat, holding a ceremonial flower in his hand.” According to Steiner-Prag, Rilke put into words what the young literati of the time intensely felt. In one early collection, Larenopfer, or Offerings to the Household Gods, Rilke expresses the charm of the various, disparate aspects—Czech and German, Catholic and Jewish—of his home culture:

They move me so

Bohemian folk songs

that quietly slip into the heart

that make it feel heavy.

Despite all this empathy, he himself remained generally isolated.

To continue the incongruities, Rilke is acclaimed for writing some of the most sublime poetry ever composed: the Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus. But Rilke’s popular fame in both German and English is based on two separate, and highly uncharacteristic, prose pieces. His first and biggest bestseller, The Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christoph Rilke, glorifies a soldier killed in battle in the 17th century. Even Rilke himself was not quite sure why this short work with a long title, which he did not consider his best, was a runaway hit. Rilke was around 20, and still marked by his experience in military school, when he first sketched out the bouncy prose glorifying defense of the homeland. He wrote based on the likely misconception that Cornet Christoph Rilke was an aristocratic ancestor of his. An early version from about 1897 was revised for publication in 1905, then again for a larger 1912 edition, which immediately sold out. During the severe hardships of World War I, just as the author was becoming deeply disillusioned with militarism and nationalism, this odd prose poem took on a life of its own. Cornet has never been out of print, and more than a million copies have been sold.

In his autobiography, the critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki—sometimes called the “pope of German literature”—almost apologetically describes his enthrallment on hearing Cornet read at a meeting of his Jewish youth group in 1930s Berlin, even as the Nazis were closing in. A member of the group turned off the lights and came out to the podium with a small lamp. Wearing an old military cape, he opened a slender book and began ceremoniously reading. Reich-Ranicki, long after surviving the horrors of the German military occupation of Poland in World War II, writes, “For me these words have never lost their charm. The magic of the rhythms has not faded.” All this for a work glorifying a military officer’s life and death! Why did a group of persecuted Jewish teenagers find inspiration in Rilke’s militaristic, chivalric themes? Reich-Ranicki goes on to explain that Cornet now strikes him as syrupy, sentimental, precious, pretentious, and very easy to ridicule in its melodrama—yet, writing in old age, he still nurses a love for the piece out of respect for the dreams of youth. Rilke’s biographer Freedman provides a clue to the ballad’s enduring appeal: the rich acoustics and rhythmic language. Although this short piece doesn’t have Rilke’s usual, highly original rhymes, the sounds are mesmerizing. But that effect in German would not explain why the work is still read in English translation and not assigned to the trash heap of sentimental war literature.

Probably Rilke’s most popular work in English translation is also prose, not verse: Letters to a Young Poet, the source for Lady Gaga’s tattoo. Rilke’s “advice”—“Go into yourself,” treasure stillness, don’t fear being alone—has now become a widely distributed cliché in American self-help literature. Rilke was acquainted with the new practice of psychoanalysis and even met Freud, although he declined to undergo it himself. He was acutely aware of his own psychological problems, but his feelings about therapy, like much else, were mixed.

Franz Xaver Kappus, the young poet who received these letters, was a 19-year-old student looking for a mentor in Rilke, who was all of 27 years old at the time. Kappus would go on to publish the Letters after Rilke’s death, apparently without the author’s approval. In 2019, the eminent Rilke scholar Erich Unglaub published the other side of the correspondence, long thought lost. Unglaub found Kappus’s letters in the Rilke family archives, which had been closely guarded until the German Literary Archives in Marbach acquired them in 2022. Among the newly available documents is Kappus’s final letter to Rilke, written in January 1909 from a military post at the Austrian border on the Adriatic coast. The poetry-loving soldier describes comrades caught in a violent storm in beautiful and moving prose: “[They] would also perhaps call out and only be answered by the wind, by the storm that steals the sound from their lips and mocks their childish powerlessness.” One cannot help but wonder, as Unglaub suggests, whether these images were in Rilke’s mind in 1912 when he wrote the first Duino elegy from a castle perched on the Adriatic Sea, envisioning angels in the gathering storm: “Oh and the night, the night, when the wind of the universe / bites at our faces—” Maybe the literary influence went in both directions.

In 2025, Sandra Richter, the director of the German Literary Archives, published a biography using these newly available documents. What emerges is revelatory, but instead of clarifying the inconsistencies in Rilke’s life, Richter adds a whole new layer of complications. For instance, Rilke was neither model son nor husband—he was not above making disdainful remarks about his mother and his wife to friends and lovers. But the letters he wrote to those close to him—including those women—show another, more complex side, with expressions of endless longing, admiration, and even intermittent devotion. Longstanding clichés about the author’s life need to be reevaluated.

Of particular interest is Richter’s analysis of the relationship between the poet and his remarkable publishers, the husband-and-wife team of Anton and Katharina Kippenberg. Richter is direct in her conclusion: Without the Kippenbergs, Rilke would have been a lesser writer—less able to travel, less exposed to new stimuli, and thus less able to develop his talents. When Rilke had writer’s block and couldn’t finish his lone novel, the Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, the Kippenbergs invited him into their home, pampered him, and supplied a secretary to take down the rest of the work by dictation. The mutual trust they developed should be seen as a landmark in literary history.

Though some of this has long been known, what is new is the extent of the Kippenbergs’ energetic support for Rilke throughout the devastation of World War I, when Anton was drafted and Katharina took over managing the publishing house, and then during the financial catastrophes that followed. They rallied some of the most influential people in Germany and Austria to protect the poet from what could have been fatal military service. They also did their best to support Rilke’s wife and daughter throughout his many ups and downs, more out of a sense of duty than self-interest. None of this was easy. Even in 1905, the rights to Cornet had to be extricated from the original publisher, who brought out only small, expensive editions. In 1912, the Kippenbergs were finally able to make Cornet the first of the now-famous Insel-Bücherei editions: thin, inexpensive pocket-size books wrapped in distinctive decorated papers. After Cornet, the other books followed in uneven succession, each requiring lots of handholding to bring to completion. Rilke’s New Poems, with its delicate verses about a bowl of roses, has never been out of print. The Insel series has continued through wars, blanket bombings, depressions, financial collapses, military occupations, political divisions, and finally reunification. Now the library of thin volumes numbers something like 2,000 titles. Old copies can easily be purchased used, sometimes with pressed flowers or clippings tucked between the pages. (Appropriately enough, Sandra Richter’s biography is published by Insel Verlag, although in standard format.) This inexplicable relationship—between a hopelessly impractical, unworldly writer and a business-minded couple surviving in merciless circumstances—might be one of the biggest paradoxes of Rilke’s life.

As his life came to an end, with the Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus just barely finished, Rilke focused on cultivating the rose garden outside his medieval stone tower in Switzerland. Early in his career, he had told friends of placing rose petals on his closed eyelids for comfort. Later on, Rilke took to writing odes to roses in French. Famously, his severe reaction to a cut from a rose thorn led his doctor to diagnose him with fatal leukemia. A year before his death, Rainer Maria Rilke played on his own name (reiner—pure, perfect, clear) in the poem that became his epitaph, written on October 29, 1925:

Rose, oh reiner Widerspruch, Lust,

Niemandes Schlaf zu sein unter soviel

Lidern.Rose, oh pure contradiction, desire

To be nobody’s sleep under so many

eyelids.

As the archives continue to be plumbed, more incongruities will likely emerge. “Pure contradiction,” it turns out, is an essential, if elusive, part of Rilke’s enduring popularity.