The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live, and Die by Keith Payne; Viking, 256 pp., $28

Keith Payne, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of North Carolina, is intent on showing how the problem of inequality operates within the human mind. He does not claim to have studied the historical causes of the American class system, nor does he aim to explore the political or cultural ideologies that have been used to rationalize differences between the haves and the have-nots. His singular focus is on how the brain is evolutionarily wired for ambition and justice alike. When societies such as ours deviate from the primitive sense of fair play, he asserts, everyone suffers.

Payne writes about both poverty and the broader condition of “feeling poor,” which affects not just the actual poor, but also many people in the middle class. For Payne, inequality is a malaise that leads struggling Americans to engage in risky, self-defeating behaviors, while simultaneously strengthening a self-serving conclusion among Americans who have become steadily richer: namely that the system works.

To tell his story, Payne intertwines two narrative voices—one left over from his poor-boy past in Kentucky, the other of the erudite thinker he has become. His youthful experience informs the story every bit as much as statistical information gleaned from psychological experiments meant to offer clues to the hidden “logic” of human behavior. Sociologists use the term alienation for the phenomenon he describes, and historians have studied status anxiety as well, but Payne is interested in psychic pain and the social costs of failure. As he amply shows by citing compelling examples from scientific research, the brain masks the degree of inequality we perceive, and most Americans assume our society is far more egalitarian than it is.

Scholars have discovered that most people grossly underestimate the amount of wealth on either side of the economic scale. They are not even close when it comes to the salaries of CEOs, estimating that they earn 30 times what an average worker takes home; in fact, it is 350 times. Assembling a group of 5,000 American participants, researchers in one remarkable study asked the subjects to compare pie charts of the wealth distribution found in two unnamed countries. As it turned out, 92 percent of the participants chose Sweden over the United States as the place they wished to live because of its greater economic equality. This held for both Democrats (94 percent) and Republicans (90 percent).

Ignorance is not bliss, however. The macro-level deception conceals a more dangerous conflict between evolutionary impulses for status and power and our survival instincts to live in a world (which Payne traces back to the hunter-gatherer stage) that relies on sharing resources. The ladder is broken, he writes, because human beings can’t forgo their desire for status, and yet are like hamsters on a wheel, chasing a dream that gives them little satisfaction. The top is so far out of reach that ambition generates debilitating levels of stress and depression, and makes the most emotionally vulnerable among us prone to risky behaviors such as outbursts of rage on a plane, sabotage at work, or taking drugs to deal with the emotional pain. Health and happiness are sacrificed in pursuit of unobtainable goals.

Neither conservative nor liberal rationales address this problem. Hard work and talent are no more important than chance and privilege in determining success, and a lack of character or a constricted social environment does not alone explain the mental poverty trap. Humans are creatures of instinct and improvisation, and poor people who live in precarious situations adapt and devise different rules for survival—what Payne identifies as the “fast strategy,” to “live fast, die young.” More successful, middle-class Americans will defend the hard work explanation even when they know from experience that rewards are allotted randomly. No one, Payne insists, can avoid that evolutionary craving for status, which leads people to constantly evaluate where they are on the ladder, subconsciously comparing themselves to others. Once again, average Americans conceal this impulse, often convincing themselves that they care more about love, faith, loyalty, and integrity. But it’s not true, writes Payne. All we need are a few primate studies to remind us that the hunger for status is what the proto-psychologists of the 18th century considered to be an “animal passion.”

Beyond its case studies, the memoir portion of Payne’s book is compelling in its own way, and is a counternarrative to J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. The Broken Ladder is a liberal man’s view of his own rise. From the first chapter, he lets us know that he remembers the feeling of shame he had as a poor child. One memory of worthlessness stands out: A new lunch lady at school asked him to pay for his meal, and he didn’t have the money. As a poor kid, he wasn’t supposed to pay, but all at once, he recognized that he had been lowered in the eyes of his peers. Comparison is at the heart of Payne’s system of inequality, so it is not surprising that he offers symbolic contrasts between himself and his working-class sibling. We encounter his brother Jason as a kid picking tobacco as the tar turns his hands black. We meet him again as he recklessly drives his pickup truck. He spends eight years in prison, while his author-brother lands a prestigious post at the University of North Carolina.

The most disturbing tale in the book involves the author’s uncle Sterman, an alcoholic living in an abandoned barn at a landfill. When diagnosed with lung cancer, he chooses whiskey over painkillers. This decision would seem irrational to most middle-class Americans, Payne writes. Yet the cause, I suggest, has a much longer history. His uncle was a quintessential squatter, part of a long line of hoboes and landless poor who live on the margins of society and contest its rules. They dismiss middling sensibilities and reject the masculine value of hard work. That is to say, the “broken ladder” of Payne’s concern long predates today’s crisis; it only looks new because the one percent have gained the lion’s share of the nation’s wealth only in the past 50 years.

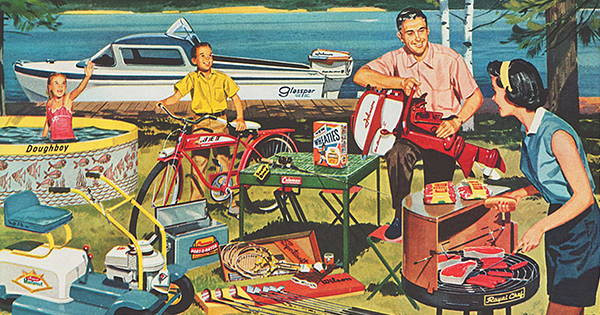

This historical element is what is missing from Payne’s book. Status may be a part of our brain circuitry, but it has also been conditioned in us over time. Our present interest in inequality comes principally in response to the obsession with status that arose after World War II. The historian Richard Hofstadter won the Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Reform, his 1955 study of “status anxiety.” Vance Packard’s influential best seller The Status Seekers appeared in 1959. This was no coincidence. The postwar creation of a stable middle class encouraged parents to expect that their children would do better than they had done. The emergence of the homogeneous class environs of suburbia and the rise of the white-collar corporate ladder created the perfect breeding grounds for a personal preoccupation with status. Payne is right to conclude that status is not new, but it is crucial to add that the rules we now live by were shaped by the “ideological toolbox” of the 1950s.

Despite this omission, Payne’s book will make its readers pause to consider the human condition in more depth. Some will no doubt conclude that the ladder-in-our-minds has become so dysfunctional that in 2016, voters elected a president whose life has long been consumed by a craving for status. The serious disability, which Payne underscores, of casting votes based on feelings over facts fits all too neatly, and that’s scary. Wishing for a quick fix (“Make America Great Again”) means that those in Donald Trump’s column were so desperate that they refused to plan for the future and instead adopted the “fast strategy,” by betting all their chips on one very risky choice. The sad conclusion this book compels is that Americans are so out of touch with reality, and so hobbled by mental crutches, that social inequality will remain the dirty little secret that we cannot possibly purge.