Warrior Eros

How an army of homosexual men became one of the most elite fighting forces of the ancient world

The Sacred Band: Three Hundred Theban Lovers Fighting to Save Greek Freedom by James Romm; Scribner, 320 pp., $28

In Plato’s Symposium, a dramatization of a drinking party, each guest delivers a speech in praise of Love. The first, a certain Phaedrus, describes how Eros, the Greek name for the god of love and for the primal force of erotic attraction, could be the basis for an invincible army of male lovers (translated by Benjamin Jowett):

And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonour, and emulating one another in honour; and when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.

The evening is set in 416 BCE, during the Peloponnesian War, but Plato composed his work decades later, after Sparta’s defeat of Athens. While Phaedrus’s speech seems to describe a hypothetical army, even for Plato’s early readers, it would have seemed either an anachronism or a prophecy. They would have been aware of an actual elite military unit, the Sacred Band of Thebes, made up of 150 pair-bonded male couples. Undefeated for three shining decades, the Band, “though a handful,” did indeed “overcome,” breaking the iron stranglehold of bullying Sparta, and freeing an enslaved population.

Athenian writers mocked the people of Thebes and Boeotia for being country bumpkins, but Thebes was rich in mythology, had produced poets such as Hesiod and Pindar, and boasted two gods as native sons: Dionysus, son of a Theban princess, and Heracles/Hercules, who labored his way to immortality. Between democratic, imperial Athens and oligarchic, totalitarian Sparta, Thebes and Boeotia represented a third way, a bold experiment in democratic federalism, its cities even sharing a common coinage. Thebes, however, had committed the sin of “medizing,” siding with the Persians during the Persian invasion. Athens and Sparta never let them forget it.

Perhaps Thebes is getting a second chance in the limelight. There is a new state-of-the-art museum in Thebes itself, and Paul Cartledge has recently published Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece. Now comes James Romm’s sensitive account of the Sacred Band.

In Athens and Sparta, romantic, erotic, and sexual relationships between men were largely countenanced and conventional: a couple was composed of an erastes (the lover), the older partner, and the eromenos (the beloved), a youth on the cusp of manhood; “lovers and their loves.” The pro-Spartan Athenian historian Xenophon seems to have been atypical in his disapproval of male-male sexual relationships; in ancient Greece it was arguably unwavering heterosexuality that was “queer.”

But if, as Romm points out, in Athens and Sparta “male erôs was ‘complicated,’” in Thebes and Boeotia it was sanctioned by the state. Male couples could take an oath at the grave of Iolaus, Hercules’s own beloved, to live together as syzygentes—yoke mates—a term that elsewhere indicates a lifelong marital bond. It is etymologically related to “conjugal.” (The modern Greek word for “spouse” is still syzygos.) After running a junta of Spartans out of Thebes in 379 BCE, the Thebans turned their attention to defense. What Thebes needed to keep Sparta’s hoplites (heavily armed infantry) at bay was an elite squad of its own; thus was born the Sacred Band of 300, its couples having sworn the “sacred” oath at Iolaus’s tomb.

The man who would lead the Sacred Band to greatness was Epaminondas. From a down-at-heel aristocratic family, he had been taught by the philosopher Lysis, one of the last Pythagoreans. Epaminondas was unsuperstitious, indifferent to worldly wealth, well-versed in literature, and an accomplished musician. He never married or had children.

In 371 BCE, at the Battle of Leuctra, the Sacred Band shattered the myth of Sparta’s supremacy. Greek hoplite warfare was a formalized affair: the strongest part of each army, placed on the right flank, first faced the weaker left flank of the opposing army. Epaminondas instead placed his Sacred Band on the left, to break the might of the Spartans from the top down. The rout was so complete that a Spartan king perished in the battle, the first to do so in generations. Epaminondas proved that Sparta was beatable; never again would it rise to military dominance.

Epaminondas and the Sacred Band pushed deep into Spartan territory, liberating Arcadia and Messenia. The latter was the traditional homeland of the helots, an indigenous population that had been enslaved by Sparta for centuries. Epaminondas not only freed the helots of the area and invited diaspora Messenians to return, but he built a city for them with massive stone walls and public buildings, constructed in an astonishing 85 days. A walled city of free helots so near to their city enraged the Spartans and helped to keep them in check. But the brilliant career of Epaminondas was cut short; he fell in the midst of victory, struck by a Spartan spear at the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE. Confronted on his deathbed with his childlessness, he declared his victories, Leuctra and Mantinea, to be his immortal daughters. He was buried on the field, beside his own “beloved,” Caphisodorus.

Thebes almost immediately went into a decline. In 338 BCE, the Sacred Band was annihilated at the Battle of Chaeronea by Philip of Macedon and his son, Alexander (soon to be the Great). Philip, who had spent his youth in Thebes as a kind of hostage, is said to have wept at seeing the Band lying all broken and jumbled together. Plutarch quotes him as saying “Perish all those who suggest that these men did or endured anything shameful.” The Battle of Chaeronea marked the beginning of the rise of Alexander, who would eventually wipe Thebes off the map, razing every building except the house of the poet Pindar. Thebes’s moment in the sun had passed.

Romm’s book not only details the history of the Sacred Band, but illuminates this murky and murderously internecine period of Greek history. He also offers glimpses into reception of the Band (a beacon for closeted Victorian homosexuals, for instance) in later eras. Romm has an eye for interesting characters—such as the sociopathic tyrant Jason of Pherae, who made his spear into a god. Or the Boeotian courtesan and legendary beauty Phryne, who offered, with her well-gotten gains, to rebuild the walls of Thebes that Alexander had knocked down so long as they bore an inscription to that effect. (No one took her up on her offer.)

Pausanias, the ancient Greek travel writer, described the monument that was erected to the memory of the Sacred Band on the polyandrion (mass grave) at the battlefield of Chaeronea:

As one approaches Chaeronea, there is a tomb of the Thebans who died in the battle with Philip. No inscription adorns it, but a monument stands over it in the form of a lion, the best emblem of the spirit of those men.

The precise site of the battle had been forgotten by the modern era; in 1818, a young British traveler out riding in the area, with Pausanias as his guidebook, literally stumbled on a chunk of marble. It proved to be the fragment of a monumental marble lion—a chunk of head and neck that alone weighed three tons.

Over a half century later, in 1880, with Greece now an independent nation, a sculptor sent to reconstruct and set up the broken lion tested the ground beneath it to see if it could hold up under the weight. What he found instead was a mass grave. A young Greek archaeologist, Panagiotis Stamatakis, performing modern rescue archaeology, discovered and made notes on 254 skeletons, an electric discovery that made The New York Times. The graves were re-covered; Stamatakis, who took ill and died during the excavation, never published his findings, and his notebooks were presumed lost. Because the skeletons did not make up a round 300, some scholars even doubted whether this was indeed the gravesite of the Sacred Band.

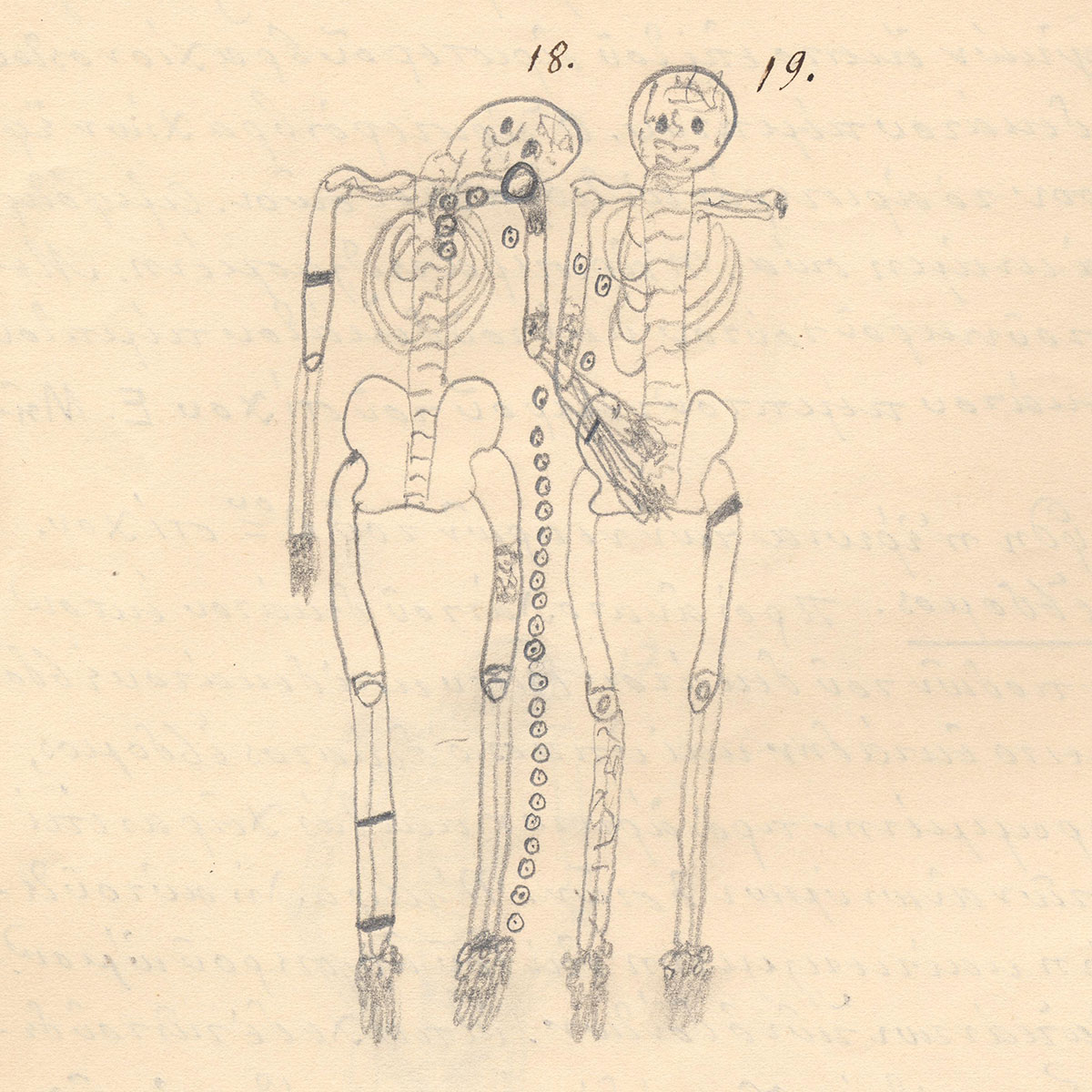

Perhaps the most surprising thing in Romm’s book of eye-opening stories is in an appendix. With the help of a scholar and translator in Athens, Brady Kiesling, Romm discovered that the notebooks still existed in the archives of the Greek Archaeological Service. Stamatakis had not only taken detailed measurements, but had drawn every skeleton with its position and wounds. It is hard to overestimate how ahead of its time this work was—consider, for instance, Schliemann’s aggressive excavations of the same decade, crashing through prosaic historical layers to get to treasure gilded with epic poetry.

Rather than being buried with weapons or armor, the bodies were buried with libation cups and strigils—the sweat-scrapers of the gymnasium, that staging ground of male eros. The skeletons, touchingly individual, ornament the book, dancing through its pages. With the help of Stamatikis’s notebooks and a digital artist, Romm was able to reconstruct the positions and attitudes of all the skeletons, which are arranged as a phalanx of six or seven rows, as if in a last stand against death itself.

With some pairs of skeletons, movingly, one seems to have an arm over the other; some others appear to be linked at the elbows.

One of the sketches from Panagiotis Stamatakis’s notebooks (courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, Directorate of the Management of the National Archive of Monuments, Department of the Historical Archive of Antiquities and Restorations)