When both you and your wife are magazine editors and simultaneously on deadline, and you’re in quarantine in a small house with your 10-year-old daughter, the hushed and fevered intensity of the workday, the constant clattering of computer keyboards, will inevitably be broken by that universal lament of adolescence: I’m bored. My daughter’s school has begun online classes, but nothing resembling her normal schedule, and so there are moments, when I’m trying to unravel a tortured paragraph or fashion a workable headline, that she’ll be hovering, looking for attention.

Which is when I recall some of the best parenting advice I ever received, delivered, remarkably enough, in the spring semester of my senior year in college—by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s eldest son. It came by way of a Slavic literature course I was taking that was taught by Herman Ermolaev, who died last year at age 94. In the blinkered ignorance of youth, I knew nothing of his backstory: captured by the Nazis during their invasion of the Soviet Union, he managed to escape, emigrated to the United States by way of Austria, earned his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley, and became a leading scholar of Russian literature. His class syllabus included most of the heavyweights: Dostoevsky, Pasternak, Zamyatin, Solzhenitsyn. It was a formidable lineup, a grand accounting of the Russian soul, but the course required only two short papers, and it was universally regarded as a gut—a prime target for the members of the administration and old guard graduates who fervently believed that grade inflation would surely precipitate the decline and fall of the American empire.

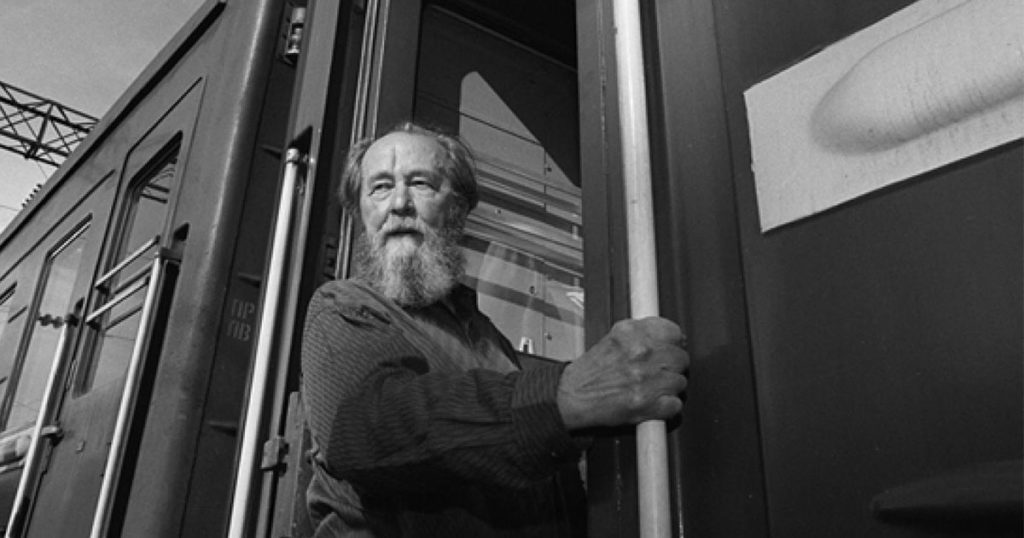

Lectures were held twice a week in the evening, and one spring night, while inhabiting that dreamlike state of suspended reality when one’s thesis is finished but the real world remains at safe remove, I wandered into a Gothic revival lecture hall and discovered Yermolai Solzhenitsyn, then a graduate student, at the front of the classroom. Invited by Ermolaev to give a guest lecture, Yermolai, as I recall, was less interested in explicating the themes of his father’s work than in giving us insight into his character. Yermolai was six when his father, after being expelled from the Soviet Union, settled in Cavendish, Vermont. There, from the isolation of a three-story writing retreat he built next to the family’s farmhouse, Solzhenitsyn embarked on one of the most productive periods of his career, working on The Red Wheel, his multivolume opus about the Russian Revolution. Yermolai spoke of his father’s work ethic (Solzhenitsyn would rise at six, have a cup of coffee, and, after a short lunch break, work late into the night) without any trace of bitterness: the writer wasn’t always around, yes, but when he was, the time was meaningful. They would scan the night sky together, his father identifying the constellations; or the elder Solzhenitsyn would give math lessons, maybe quiz his son on readings he had assigned. Their moments together were all in the service of giving the boy a greater understanding of the world, revealing its secrets in recurring mini-lectures. Yermolai expressed profound gratitude for his upbringing—a model worth following during these harried days of quarantine, even if we never approach Solzhenitsyn’s superhuman commitment to seclusion.