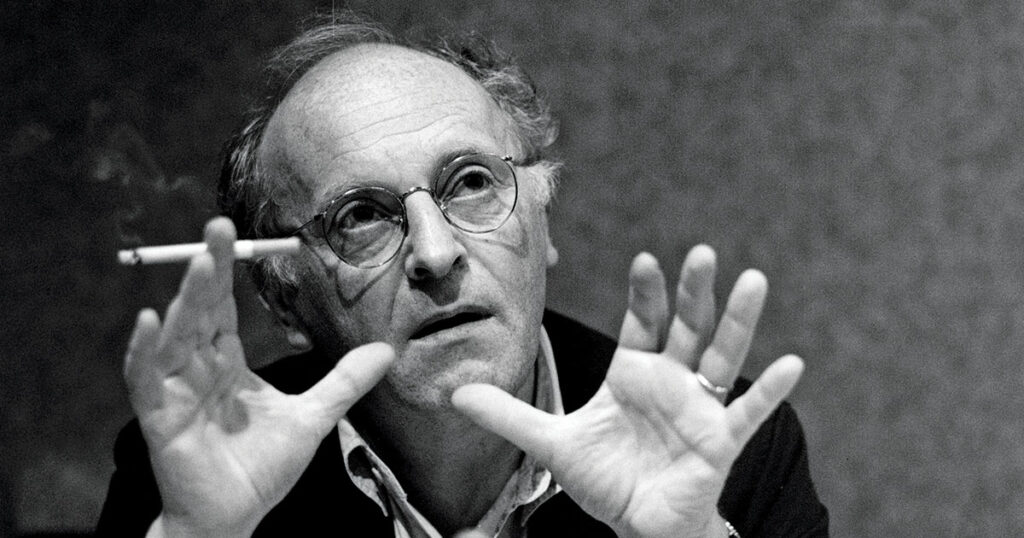

Joseph Brodsky would have turned 80 in May, but anyone who knew him in the 1980s or ’90s would find it absurd to imagine him as an octogenarian. His robust presence, which commanded any room back then, was incompatible with the idea of his shrinking into doddering frailty. But Brodsky was both young and old. His energy, his probing mind, the rakish slant of his shoulders, his reach-for-the-rafters poetry readings—these qualities kept him ever clothed in the semblance of youth, a boy genius in secondhand jackets that looked as if they came off the rack wrinkled and ink stained, yet draping him like a monument. But he also seemed old. Watching him chain-smoke Kent III cigarettes, having first bitten off the filter, despite two bypass surgeries, made his death from a heart attack in 1996 at age 55 seem a terminus already ticketed. And long before ill health carved a certain tiredness around the eyes, he exuded the aura of someone who had lived more deeply than most, been through much more. His slate-blue peepers looked not only across rooms, but centuries.

This gaze suggests the mien behind his poetry. Even when they first appeared, Brodsky’s poems spoke to the moment, but also through it. At the conclusion of “Eclogue IV: Winter,” translated from the Russian by himself, he captures the passing feel of writing on a page while also making the case for its permanence:

Cyrillic, while running witless

on the pad as though to escape the captor,

knows more of the future than the famous sibyl:

of how to darken against the whiteness,

as long as the whiteness lasts. And after.

The urge to consciously speak across time, coupled with Brodsky’s ability to inject his own speaking presence into the poems, accounts for their high degree of self-reflexivity. As he writes in “A Part of Speech,” the poem that more than any other placed him on the world stage, “What gets left of a man amounts / to a part. To his spoken part. To a part of speech.” Throughout his poems he makes constant reference to the fleeting and visceral act of speech itself, so much so that it is often hard to know where the man stops and the poem begins. Because Brodsky seems to be talking out loud in his poems, they can feel more recorded than written, no matter their loyalty to rhyme and meter. His friend and fellow Nobel laureate Derek Walcott shared his fondness for allusions to the pen crossing the page, but for Brodsky, the poem becomes a theater in which he commands center stage, drawing the reader in not just as a reader but also as a spectator at a drama.

As with Walt Whitman, Brodsky’s persona fuels the engine of his poems. The difference is that whereas Whitman wished to infuse a single individual with a collective consciousness, Brodsky was bent on describing, free of cant or self-justification, not only what it means to be a human being but also what it means to be this human being. Persecuted and interrogated by the Soviets, twice thrown into mental institutions, and finally denounced and sentenced in 1964 to five years’ hard labor in the Arctic (though released after 18 months), he’d already had quite the life before he was “invited” to leave Russia for good in 1972. As his mentor Anna Akhmatova quipped, “What a biography they’re fashioning for our red-haired friend!” Though the psychological and physical toll was no doubt staggering, he rarely spoke of it. But what had happened to this human being was enough to destroy almost anyone.

I met him in 1981, when I took his poetry seminar in the graduate writing program at Columbia, but really it was years before that I had dipped into his Selected Poems of 1973, and then most pointedly into A Part of Speech when it was published in 1980. The opening of the latter’s title poem still rests in my ear to this day in George L. Kline’s translation:

I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland

by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on

in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice

that ripples between them like hair still moist,

if it ripples at all.

Just months out of college, reading this at night after spending my days building stone walls in a terraced garden in Wales, I felt transported. Here was a poet who in only a few lines could wed nature, birth, rhymes, and the speaking voice, all of it laced with a melancholy born of the lament laid down in Kline’s translation of “Odysseus to Telemachus”:

Telemachus, my son!

To a wanderer the faces of all islands

resemble one another. And the mind

trips, numbering waves; eyes, sore from sea horizons,

run; and the flesh of water stuffs the ears.

I can’t remember how the war came out;

Even how old you are—I can’t remember.

Given that I was the son of a truck driver and the sole sibling or cousin to earn a BA degree, and that I wrote poems, had traveled in Europe, and had no prospects of a job or career, it might be tempting to read something Oedipal into my response. But I was not out to slay the father, or even to deny my own, whom I loved dearly. Rather, I felt the desire to become a different kind of son, to serve something larger, something older. A few months later, I turned in my mason’s trowel for a plane ticket, headed home, and applied to Columbia.

There, in what can only be described as the Soviet glumness of Dodge Hall, Brodsky would hold forth for two hours each Tuesday. Hardy, Frost, Cavafy, and Auden were the main fare, as well as Wilfred Owen, Osip Mandelstam, and Marina Tsvetaeva. Brodsky was not the most elegant of classroom managers, to say the least. His method mainly consisted of asking a question for which he clearly had the answer, and then proceeding to quietly reply to any student response with either “Garbage” or “Pretty good.” (I once received a “Pretty good—in fact, that’s awfully good!” at which point it felt as if the heavens would burst into chorus.) Described this way, Brodsky’s method sounds like a nightmare, and I’m sure for some it was, but for many of us the performance was mesmerizing.

From three to five P.M. on those darkening fall afternoons, we felt that we were not so much in the presence of a poet, and certainly not an academic or a scholar, as of poetry itself. Nothing of this man’s thinking was held back, and it seemed as if he were making his case for poetry to the spheres rather than to a roomful of graduate students. Yes, he could be rude, and no, none of us ever got our essays back with any kind of useful comments, if we got them back at all. And he could be wrongheaded (his case for reading Frost’s “Home Burial” as a tragic rendering of Pygmalion’s love for Galatea seemed a stretch) or even flat wrong (Brecht and Neruda are not second-rate poets—they were just Marxists; Nabokov is not a “failed poet,” just a fellow genius of a different stripe). But once you found your way past the manner, you got to the matter: a whole and almost molecular engagement with what poetry can be, why it matters, and why it is the very manna of thought and feeling when read seriously.

This kind of gravitas remains the central attraction of Brodsky’s verse. He pegged poetry as “the supreme form of human locution in any culture,” representing “not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon” (from his essay “An Immodest Proposal”). Although these ideals might seem too lofty for the marginalized art of poetry to bear up under today, they were at the core of what he felt to be his charge as a teacher. Agree with him or not on any particular poet or poem, there was no ignoring what he handed over freely to his class, and what he cites elsewhere in the same essay, namely, that poetry “is the only insurance available against the vulgarity of the human heart.” Reading poetry, “you become what you read, you become the state of the language which is a poem, and its epiphany or its revelation is yours,” and the same could be said for his teaching.

Revelation is what his poems still offer. This seductive quality helped seal Brodsky’s standing in the 1980s, especially after the publication of A Part of Speech. In “Lullaby of Cape Cod,” one of his best poems, beautifully rendered in English by Anthony Hecht, Brodsky’s voice is front and center when he observes, “The change of Empires is intimately tied / to the hum of words, the soft, fricative spray / of spittle in the act of speech.” A few lines later, however, a shift occurs from the act of speech to the poet’s own immediate bodily presence:

In general, of all our organs the eye

alone retains its elasticity,

pliant, adaptive as a dream or wish.

For the change of Empires is linked with far-flung sight,

with the long gaze across the ocean’s tide

(somewhere within us lives a dormant fish),

and the mirror’s revelation that the part in your hair

that you meticulously placed on the left side

mysteriously shows up on the right,linked to weak gums, to heartburn brought about

by a diet unfamiliar and alien,

to the intense blankness, to the pristine white

of the mind, which corresponds to the plain, small

blank page of letter paper on which you write.

Notice how he moves from the eye to the mirror, to the part in the hair, to the gums, heart, mind, and finally, and pointedly, to the blank page on which he writes, perhaps, the lines we are reading. A couple of pages later in this long, marvelous poem, this implied inner voyeurism turns into the full-fledged assertion of the poet speaking and writing in unison:

I write these words out blindly, the scrivening hand

attempting to outstrip

by a second the “How come?”

that at any moment might escape the lip,

the same lip of the writer,

and sail away into night, there to expand

by geometrical progress, und so weiter.

If this were not enough to allow the reader to inhabit the poet sitting at his desk, the poem hands itself off to the reader more and more as it progresses, especially when Brodsky asks us to

Preserve these words against a time of cold,

a day of fear: man survives like a fish,

stranded, beached, but intent

on adapting itself to some deep, cellular wish,

wriggling toward bushes, forming hinged leg-struts, then

to depart (leaving a track like the scrawl of a pen)

for the interior, the heart of the continent.

The poem, having traced the evolution of the poet’s speech in attaining landfall through “the scrawl of a pen,” invokes our own evolution as well. The illusion is that we are no longer just readers of the poem, but rather a part of the poem, Brodsky’s inner monologue and thoughts played out as if our very own voice were speaking to ourselves. Indeed, “Lullaby of Cape Cod” may essentially be about a poet talking to himself inside a room, but what a room it is. If its 412 lines were not enough to demand our total immersion, its journey into and through the void epitomizes what Brodsky felt was the core strength of American poetry as set down by Frost in “A Servant to Servants,” namely, that “the best way out is always through” (quoted in Brodsky’s essay “Speech at the Stadium” and elsewhere). The poem shows him not only at the height of his powers but also having conquered the dire circumstances of exile, grief, and loss that would have derailed most other people.

This drive carried over to the classroom. As one cold December day faded into night outside Dodge Hall, he got to the end of two hours on Frost and said to the class, “I need another hour, who can stay?” Half my classmates reached for their coats and knapsacks, but the rest of us settled in. What followed, however, was not a class but an hour-long monologue, Brodsky’s brow breaking into sweat as he dragged hard on those Kent IIIs and conversed with the back of tomorrow. Much of what he said can be found in the title essay of his 1995 collection On Grief and Reason. That essay focuses exclusively on “Home Burial” and Brodsky’s insistence that

This is a poem about language’s terrifying success, for language, in the final analysis, is alien to the sentiments it articulates. No one is more aware of that than a poet; and if “Home Burial” is autobiographical, it is so in the first place by revealing Frost’s grasp of the collision between his métier and his emotions.

Quite the reading of Frost, one might say, but the credibility of it in relation to Frost is not the point. Instead, it is Brodsky’s reading of Frost, and not just of him, but of poetry itself, one forged with a passion and a laser-like gaze that cuts away the fat in order to get right down to what Brodsky saw as the poem’s muscle.

He did this with a number of Frost’s poems on that night until, exhausted, as if at last freed of all he had to say on the matter, he stopped. Taking a sip of coffee, he scanned the dozen or so faces still in the room before beginning with the “Vwell, vwell, vwell …” he so frequently used as a stopgap in which to load up his next thought. In this case: “Some of you will go on to become poets, though many of you will not, for that’s just what comes to pass and what statistics tell us. But there is one thing that all of you must do and that is be grateful for this language!” His eyes glistening, his hand resting on the collected Frost as if it were a Bible, that was it, the clear implication being that we should be grateful for Frost and for the English language itself.

As elementary a lesson as that may sound, it is rare to have it delivered so directly and with such passion, as well as for it to be allowed to hover in the air at the end of three hours. Brodsky’s flair for the dramatic was a pedagogical tool, for his thinking on poetry and much else was so singular, so surprising, and at times so strange that there was never a conversation to be had with him in which I didn’t learn something, nor did I have to agree with that something in order to learn, because what he set in motion above all else was thought itself. Not the limits of a meager idea, but the activity of thought itself. And that was what was so freeing, why there was more oxygen in the room when Brodsky was in it, and what I kept returning to in the years to come.

That same night after his aria on Frost, as we walked out of Dodge Hall, I had the audacity to ask if he might want to go for a drink. “Let’s try it!” he offered, and before I knew it, I was sitting at a table in a bar across the street, waiting for Brodsky to collect our drinks and wondering, what the hell am I going to say now? Wisely, I started with the only thing I could think of: “What should I read?”

Nodding his head in approval, he asked for pen and paper, and there in a little notebook I carried around he scribbled down a list: Edwin Arlington Robinson, Weldon Kees (underlined), Ovid, Horace, Virgil, Catullus, minor Alexandrian poets, Paul Celan, Peter Huchel, Georg Trakl (underlined), Antonio Machado, Umberto Saba, Eugenio Montale (underlined), Andrew Marvell, Ivor Gurney, Patrick Kavanagh, Douglas Dunne, Zbigniew Herbert (underlined), Vasco Popa, Vladimir Holan, Ingeborg Bachmann, “Gilgamesh,” Randall Jarrell, Vachel Lindsay, Theodore Roethke, Edgar Lee Masters, Howard Nemerov, Max Jacob, Thomas Trahern, and then a short list of essayists: Hannah Arendt, William Hazlitt, George Orwell, Elias Canetti (underlined and Crowds and Power added), E. M. Cioran (Temptation to Exist added), and finally the poet Les Murray added in my own hand after he suggested it. The sheet of paper, roughly the size of an iPhone but, as Brodsky would say, with far more and far greater information stored within it, remains tucked away inside my copy of A Part of Speech to this day.

What else we talked about I cannot remember, but a friendship had blossomed. The following year several fellow students approached me to ask if I might inquire whether Brodsky would be willing to do a tutorial on Russian poetry with us. Not only did he agree, but he insisted that we come to his Greenwich Village apartment on Morton Street each Sunday night, where he handed out mimeographs of translations of 19th-century Russian poets—V. A. Zhukovsky, E. A. Baratynsky, F. I. Tyutchev, Pushkin, and others—which later turned into An Age Ago, the anthology translated by Alan Myers with an introduction by Brodsky. In it he writes,

[A]n age ago, much less stood between man and his thoughts about himself than today. … That is, he knew practically as much as we do about the natural and social sciences; however, he had not yet fallen victim to this knowledge. He stood, as it were, on the very threshold of that captivity, largely unaware of the impending danger, apprehensive perhaps, but free. Therefore, what he can tell us about himself, about the circumstances of his soul or mind, is of historical value in the sense that history is always free people’s monologue to slaves.

Sunday nights at Joseph’s house, indeed! You didn’t ask that many questions, you just wrote in a notebook as fast as you could. And how freeing it all was, and how welcome we felt in that low-ceilinged bungalow, Brodsky archly muttering “Horses, horses!” to the rumbling gallop of the espresso pot as it boiled on the stove.

Graduation and a Fulbright to translate Ingeborg Bachmann’s poems (ah, that list of poets he wrote down and its trajectory) took me to Vienna for the next two years, but never quite far from Brodsky. One day a package arrived with a copy of the latest Vanity Fair, which contained his splendid essay on Auden, “A Passion of Poets,” which he wanted me to deliver to a descendant of Prince Razumovsky (of Beethoven quartets fame), who had been kind to him on his landing there in June 1972. A couple of months later another item came, from a friend of mine and wrapped as a gift. Titled J.B.–Debut, it is a chapbook containing eight poems translated by Carl R. Proffer and published by Ardis, the Russian-language publishing house he helped found. The copyright page dates it as a limited edition published in 1973 in “twenty-six copies lettered A to Z and twenty copies numbered from 1 to 20, each signed by the author.” The warm wonder of it, as a gift from a friend who knew what Brodsky meant to me, could be matched only by the lifeblood inside, such as that of the lover doomed to exile at the end of “Sonnet”:

… How often on this old deserted spot

I’ve dropped into the wire-connected cosmos

my copper coin, intaglioed and crested,

despairing, in an effort to prolong

the moment of togetherness … Alas,

a man who knows not how to substitute

himself for a whole world is usually left

to spin the telephone’s pockmarked dial

as if it were a table at a seance,

until the shade replies in echo voice

to terminal screams ringing in the night.

It was the same gift whenever a Brodsky poem appeared in a journal, magazine, or newspaper of the time. For they were not only poems, but news, missives from the outposts of Brodsky’s scattered transatlantic existence. This became particularly so in 1977, after Brodsky gained U.S. citizenship, and thus the security of a passport. Venice, Florence, Rome, Amsterdam, Paris, Mexico, Brazil, Sweden, London, San Francisco—one never knew where Brodsky was going to report from next, nor did it matter. Wherever he landed the outlook was always the same—the reason being, as he notes in his own translation of “North of Delphi,” “To man, every perspective empties / itself of his silhouette, echo, smell,” while “the pen creaking across the pad / in limitless silence is bravery in miniature.”

For many people, the stance of the globetrotting poet wore thin, seeming not so much a different orbit as a well-polished act, particularly the more his celebrity and fortune grew. Also troubling was his growing insistence on translating himself, or at best laying siege to the efforts of his faithful translators by elbowing his way into their versions with more “accurate” renderings, but versions that sometimes sounded tin-eared and clunky, their enjambment awkward and offbeat. This tension grew as Brodsky composed more and more original poems in English, many of them sounding like watered-down Auden, such as his “Bosnia Tune,” which argues, “While the statues disagree, / Cain’s version, history / for its fuel tends to buy / those who die.” But in the best of them “the wan flat voice” prevails, such as in “Törnfallet” from 1993, in which the poet imagines his widow circling a meadow in Sweden after his death, before concluding,

Now in the distance

I hear her descant.

She sings “Blue Swallow,”

but I can’t follow.The evening shadow

robs the meadow

of width and color.

It’s getting colder.As I lie dying

here, I’m eyeing

stars. Here’s Venus;

no one between us.

Or in the closing lines of “Reveille,” a poem published just a week after his passing:

Painted by a gentle dawn

one is proud that like one’s own

planet now one will not wince

at what one is facing, sinceputting up with nothing whose

company we cannot lose

hardens rocks and—rather fast—

hearts as well. But rocks will last.

Brodsky became a better poet in English, not only because his English attained near native proficiency (in the 15 years I knew him, I only once heard him search for a term he didn’t know, and that was “railroad tie”), but also because age and illness curbed his ambition, or better yet, his lack of inhibition in the grand Russian style. What did not lessen was the acuity of his vision, as well as his ability to embody what he also saw as the strength of American poetry, its “relentless nonstop sermon on human autonomy; the song of the atom, if you will, defying the chain reaction. Its general tone is that of resilience and fortitude, of exacting the full look at the worst and not blinking” (“An Immodest Proposal”).

Nostalgia is a feeling connected much more to places than to people. When asked whether he wanted to return to Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Brodsky would only say that, if he did, it would be because of a desire to see again an apartment or two, “places, not faces,” as he put it. Like many people, I miss visiting him and talking about poetry and life, but if I really think about it, the places are what I long to revisit—the apartment on Morton Street in Greenwich Village, or the open-beamed semidetached apartment at the back of Rawson House in South Hadley, Massachusetts, or drinks and dinner at what was then Woodbridge’s Inn up the street. But when revisited, they remain just places, emptied of Brodsky’s glowing presence and speech, the “Kisses! Kisses!” he offered everyone in parting. Or his quizzical advice, when I once despaired of finding a fit role in the world, “My dear Peter, don’t we all serve by default?” Or his spirited response, “Now, this is something! This is something! ” when at his kitchen table in South Hadley, I showed him a photo of my toddler twin daughters and told him one bore the middle name of Josephine.

This all came home to me on a fresh spring day in 2015 when I found myself walking past 44 Morton Street for old times’ sake. The super was outside, hosing down the sidewalk, and when I looked in through the ground-floor window, I could see the whole apartment was open and under renovation. Since no one seemed to be around, I asked if I might walk down the alley to the back garden onto which Brodsky’s former living room–study opened. I figured that just seeing the trees and brickwork patio would be a comfort, but then I saw, standing outside, awaiting disposal, the refrigerator from the old apartment, its door removed and leaning against the wall, and inside its exposed cavity the abandoned travel carrier for Brodsky’s cat, Mississippi, a name he gave it because he thought cats liked sibilants far more than fricatives. All I could think of was what the poet had told me in “A Part of Speech,” right from the start:

Only sound needs echo and dreads its lack.

A glance is accustomed to no glance back.