This year marks the 46th anniversary of the Kent State shootings, when the Ohio National Guard killed four unarmed students and injured nine others, changing the course of the Vietnam War. Days before, Richard Nixon had announced a new invasion of Cambodia, and campuses erupted in protest across the country. At Kent State, a demonstration quickly turned into riots, leading the mayor of Kent to call in the National Guard. It was during a rally of 2,000 people on the university commons that the National Guard fired into the crowd.

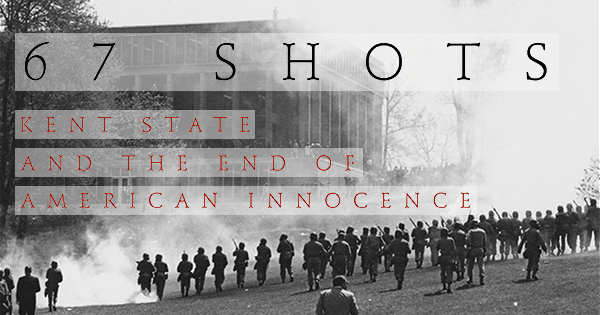

Howard Means’s new book, 67 Shots—so named for the number of rounds fired over 13 seconds—incorporates newly available oral history from the university’s archives and extensive interviews to make sense of a volatile, violent moment in America’s history. Read an excerpt from Means’s analysis of the shootings, in which “every party to the tragedy made the wrong choices at the wrong time in the wrong place.”

Later, after Neil Young’s “four dead in Ohio” anthem, after the nine wounded and the national shock and the bitter editorial recriminations in all directions, it would be common to ask: Why Kent State? This wasn’t Berkeley or Columbia or even Ohio State, about three hours southwest, where students and police had been in running battles for more than two weeks when Kent State finally erupted so spectacularly.

Kent State was commonly described as a working-class university and a local one: 80 percent of the students were from Ohio, many from surrounding counties and close-in cities like Cleveland and Akron. Admission standards were modest. By law, Kent State had to accept any graduate of an accredited Ohio high school. Someone had nicknamed the school “Suitcase U” because so many students headed home for the weekend. After-school jobs were common to help meet tuition. One popular work option as the Vietnam War heated up was the National Guard, a sure paycheck and a refuge from the Selective Service draft.

Many Kent students assumed that a kind of firewall—part demographics, part tradition, part “otherness”—exempted their school from the front lines of the war against the war. Richard Karl Watkins, an undergraduate in 1970, recalled talking only a few weeks earlier about the Ohio State unrest with one of the cafeteria workers as he stood in line at an on-campus eatery. “I remember one of us saying we were glad we were in Kent because that [kind of thing] wouldn’t happen here. We’re not like Ohio State. . . . In retrospect, it seems absurd. Seemed very real when we were talking about it.”

In fact, Kent State had a robust history of political unrest that had flown under the radar of national attention, precisely because the school was so regional. By the mid-1960s, antiwar activism was a staple of campus life, sometimes with a dramatic flair. Timothy App recalled the homecoming parade his freshman year, 1966: “All the organizations on campus built floats. The parade went right down Main Street. One float was an old, burned-out car. The members were walking in silence beside it, with gas masks on and dressed in military paraphernalia. The townspeople hated it.”

Excerpted from 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence by Howard Means. Copyright © 2016. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.