Finding Your Voice

How one writer discovered his when he stopped looking for it and learned instead to listen

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Illinois in the early 1960s, I discovered a language lab that nobody used. In it I could listen to foreign-language conversations or popular poets of the day reading their own words. The recordings were 78-rpm records, large as dinner plates—a common medium of the time along with saucer-sized 45s and reel-to-reel tapes. Did nobody use the lab because half its contents were recordings of poets? In its sheltered precincts, in a deeper isolation induced by heavy 1960s headphones, I listened to Dylan Thomas, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, E. E. Cummings, Theodore Roethke, Marianne Moore, and the fiction writer Eudora Welty.

Hearing their voices, and having heard Frost and Roethke read in person, I told myself I would like to write like them. I felt the same about Anton Chekhov and Nikolai Gogol and F. Scott Fitzgerald and James Baldwin and William Maxwell: I’d like to write like him. I was 19 and later on, older and wiser, perhaps, I sensed I didn’t want to write like any of that crew. I wanted to write like me. The sound of the headphone voices, however, added an internal dimension, I now recognize, to the developing voice I came to identify as my own.

When I was in college, what we now call a writer’s voice was generally called style. Develop a style, writing instructors would say. And by that they generally meant, according to my translation of it, that I was to construct a persona the reader would recognize by inventing a distinctive element in my prose that would identify me as that writer and that writer alone, as if I were designing and sewing an identifiable vestment.

For a writer who constructs his or her style in such a way, however, that’s how it feels: constructed. The novelist Elmore Leonard once said in an interview, “I try not to use constructions that are obviously written constructions.” After a year or more of attempting to formulate a style, I realized the admonition to do so was as helpful as saying, “Develop an extra frontal lobe.” So I started to write and write, without focusing on creating a voice, and when I had what I felt was a story, I gave it to my favorite reader, soon to be my spouse, to read. Her name is Carole—her mother likely a fan of the movie star Lombard.

Once I started to publish, I read each story to her. She knew three foreign languages my English resonated against, was a graduate of a private school, better at social situations than I. That, along with the beaches and rains of the Pacific Northwest that constituted her homebound makeup, added the breadth of the sea to my inland map. Without her saying much, I learned from her the most about my potentialities and limits. My reading to her reminded me of the recordings I heard in the language lab, and a critical resonance in her responded like radar, alerting me to false notes that jangled my senses. “I hate to botch anything,” Saul Bellow once said about his fiction. “I hate to get things badly wrong … seriously wrong.” There is a wrong.

I cut every falsity I recognized and used other words and phrases, usually simpler. I found that fewer false notes occurred when my defenses fell and I spoke directly to her. After months of this, I felt a resonance in my head when the words I wrote rose in conformation to an inner sense established by reading to her. She was free to return to real life.

How did this moment of internalized resonance occur? I’m not sure, but I suspect persistence. I think I came to the same realization that an authority on language, Charles Harrington Elster, points out in What in the Word? : “The colloquial has become our modern paragon of style and, to all but the most confident stylists, formality has become something of a sin.”

Sin, he says. Colloquial of course means words in the manner and tone and verbal arrangements as spoken. That is what voice is—not a vestment.

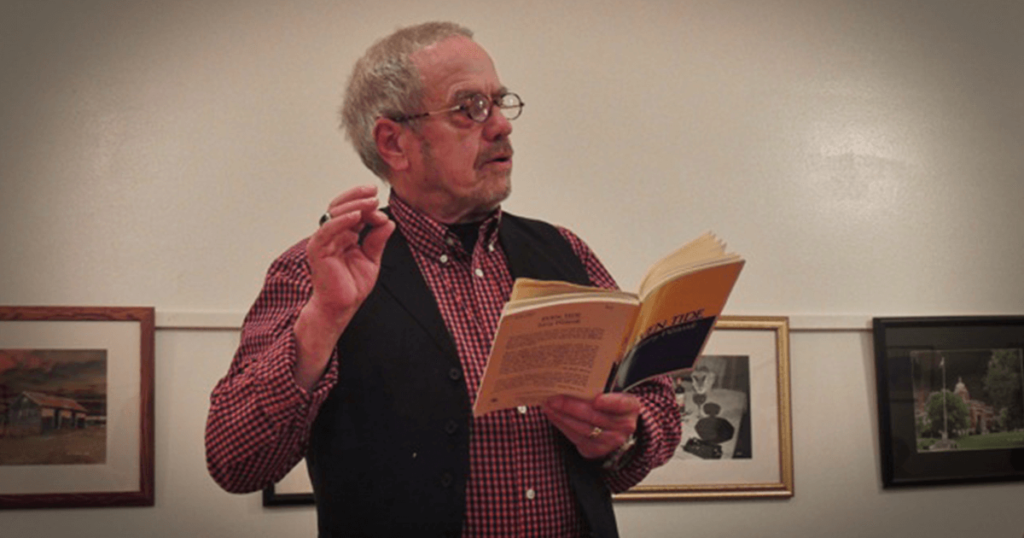

Members of the workshops I conduct read their writing aloud. What I was striving for when I began, I want beginning writers to become attuned to: the distinctive sound of their inner diction. When they read to a quorum of peers, those who will be writers hear—when words they felt were okay test the air—false notes that cause them to flinch or blush.

In 1985, two decades after my first publication, Carole sat in on a poetry workshop, a three-hour evening session. My talk that night, in a common preface to an early workshop, was about voice. She took notes, and I refer to them because I can’t speak with the authority I had at that age, the mid-40s, when most people are tempted, as I was, to assume they know it all. Age corrects that.

Voice: she wrote, and drew a dark square around the word.

—imprint of your personality on all you do or say. I didn’t begin with literary terms, because I had learned that voice is an inner essential, inborn as I register it.

—appears helplessly on the page. I’m not sure how I explained or expanded on this, but I can say my imprint appears helplessly only when I refrain from trying to impose strictures or constructions and allow it to open in a natural way, helplessly, as it were—one can’t help what one is, one can only improve on it—onto a page.

—is what and the way you are when most yourself. I was troubled at times by encouragers who said about a future moment I feared, an interview or public performance, “Just be yourself.” I wasn’t sure who that was. I was more myself when a sheet of paper lay under my hand and I was searching for words to secure a scene in a novel. The scenes appear movielike in my mind and I try to translate the visual acts of any appearance into language.

—physically a part of me; and below that she wrote innards. I suspect I was saying that my voice, your voice, is as much a part of me, of you, as our innards, indisputably so, no substitute, none other will do.

—exactly the way you talk. Yes, in the best sense, when all hesitations and backtrackings, as in, you know, like, you know, like awesome!—when all the backtracking searches for words are removed and a central inner vocal throb remains. It’s also the way you walk and dress and enter a room and speak to an amour because it’s the one-and-only you and not a style.

—every voice leaves an imprint as different as a fingerprint. I would rather I had said distinctive as a fingerprint, but this was off the cuff—as a sort of unassailable proof. No research on voice recognition was available at the time, or anyway made public, and now we know the extent of it: your spoken voice leaves an imprint as unique as a fingerprint.

A previously unpublished talk in obviously spoken prose by Saul Bellow, perhaps America’s most deserving Nobel Laureate, appeared after his death in The New York Review of Books:

[I]n my first consciousness, I was, among other things, a Jew, the child of Jewish immigrants. At home our parents spoke Russian to each other, we children spoke Yiddish with them, and we spoke English with one another. At the age of four we began to read the Old Testament in Hebrew, we observed Jewish customs, some of them superstitions, and we recited prayers and blessings all day long. Because I had to memorize most of Genesis, my first consciousness was that of a cosmos, and in that cosmos I was a Jew …

A millennial belief in a Holy God may have the effect of deepening the soul, but it is also obviously archaic, and modern influences would presently bring me up to date and reveal how antiquated my origins were. To turn away from those origins, however, has always seemed to me an utter impossibility. It would be a treason to my first consciousness to un-Jew myself.

That is why Bellow’s voice has dimensional resonance—the rough but distinct edges of his “archaic” upbringing underlie the sophisticated polish of his paragraphs. To refuse to un-faith oneself is to refuse to undo a certainty that runs like a current under all writing, whatever one’s faith may be, since writing exists in the faith that the words employed will make sense. All these are grounded within the individual voice. With a refusal as grand as Bellow’s, a writer may begin to produce, or start the course of producing, books of the kind that Bellow wrote, from Seize the Day and Herzog and Mr. Sammler’s Planet down to The Dean’s December and Humboldt’s Gift to More Die of Heartbreak and Ravelstein.

In all these, Bellow, in his quirky voice, is prophetic in predicting the spectrum of dislocations in present-day America, whether educational or racial or political or gender related, not to mention the assault of word wars on the Internet. The reason lies in his words themselves: that he refused to give up his faith, to un-Jew himself, such that the prophetic truths in his fiction are based on a moral choice that deepens his discernment. Those who retain the essence of faith, and try to shape their words toward that evasive element called truth, are aided by discernment in their depictions, as you find in fictionists from Leo Tolstoy and Franz Kafka and Albert Camus to Willa Cather and Louise Erdrich and Marilynne Robinson. At the center of any credible truth is an individual voice as identifiable as a fingerprint.

This doesn’t mean that, as a writer of faith or as one with an essence of faith, you gain the applause of an attendant crowd. Openness of voice may not enhance a novel’s reception. The clearer my voice became, the more my work met resistance. Most writers are outcasts or anyway outliers who exercise their imagination in seclusion, but the response to my work at a certain point seemed so severe that I put in a book for however long it might last, “prejudice, whatever form it takes, is a boot in the face.” That doesn’t mean a writer should necessarily write about faith, but he or she should understand that the underlying faith that informs prose has the power to offend.

The novelist-philosopher John Gardner once told me that the personality amalgam common to writers is the monster-angel. The fleet angel-being who lays down lines of glowing and impeccable prose might be on the run from an underlying monster of a writer’s true natural state. That’s at least partly what Bellow meant, I believe, when he said that you as writer will out yourself the more you pretend to be the person you are not. He noted that a writer is most autobiographical when writing about a character the writer assumes is nothing like himself at all. When a guarded self is set aside, the floodgates open, while, on the obverse, writer’s block occurs when the self feels that the monster wants to emerge. Anthony Burgess, writing about his biography of D. H. Lawrence, said, “Every book you write is fundamentally about you.”

The beauty of writing as it wanders in its offhand way across a page, or rises in arrested spiky arrangements, is its ability to set up correspondences with other perspectives, backgrounds, abilities, tastes, in a kind of spiritual kinship. The author, after all, is absent, but the vagaries of vulnerability in his or her voice allow the auditor to enter pathways that lead to a writer’s central vocal identity—you hear that? And the reader, invisible to the author, is drawn inside the work, say, of Bellow, an articulate and dissident Jew of another generation, another culture, or rests in the humane architecture assembled by the African-American novelist and philosopher Charles Johnson, the author of Middle Passage. Such voices crisscross and complement each other along with a host of murmuring others in the echoing shadowgraph of the brain—all extending themselves endlessly across a shifting handiwork of remembered pages, the instillation of each writer an expression of faith in its eventual encounter with a reader who listens.