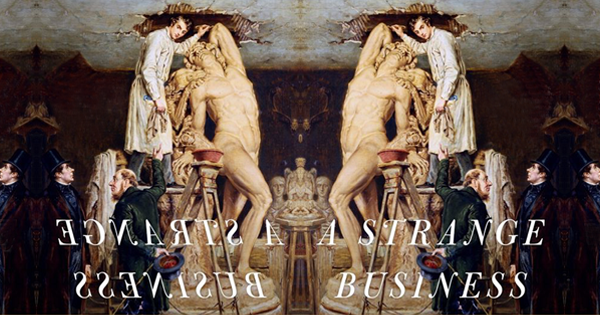

In an era in which Damien Hirst can earn $111 million at a one-man Sotheby’s show, and Gerhard Richter calls the prices his own artwork fetches at auction “completely over the top,” it’s perhaps worth asking how we got here. James Hamilton’s latest book, A Strange Business, traces the origins of art dealership in 19th-century London, when art and commerce first were wed.

At a gallery party in 1855, one representative of the age but also shockingly modern, the hired entertainment was an executioner whose chosen victim was a baker’s dozen of engraved plates, used to make prints of popular artists’ work, which were smashed into glittering pieces. The goal of the event (which was advertised in the newspaper) was “to give a sterling and lasting value to the existing copies, which by this means can never become common”—and thus cheap. “On the anvil,” Hamilton writes, “past practices in the business of art were shattered into pieces, and new systems wrought.”

Dealers and their commercial activities are fundamental to the development of the history of art. Knowledge of who owns what in any one period, how a work passed from owner to owner, and where and by whom it might have been seen is critical to a clear drafting of art history in the same way that the properties of two reactive chemicals is required knowledge before they are put into the same bottle. Had the paintings of Claude and Poussin been somehow invisible to young British artists in the eighteenth century, the history of British art would have been very different. Claude’s and Poussin’s paintings, and their imitations and fakes, came in bulk to Britain through the activities of Grand Tourists, agents and art dealers. It is the market, display and exhibition systems that these people created that gradually enabled a wide public to see art from the continent, and for a rich culture to develop out of it through the insight and energy of a new generation of artists …

By the first decades of the nineteenth century two or three generations of Grand Tourists—men and women of means accompanied by their valets, coachmen, hairdressers and tutors, and the occasional comfortable cow to produce reminders of home—had crossed the Alps or sailed the Bay of Genoa to experience the potent mix of ruin and renaissance that only Italy could adequately supply. The Society of Dilettanti—young men who gathered together for wine, conversation, song, and a good time—shared a common experience of the Grand Tour and a determination to publish volumes recording classical remains and history: ‘Esto pracelara; esto perepetua’, they proclaimed together when they toasted themselves at the end of their meetings. Travelling in hope and enthusiasm, many brought home debt, others syphilis, while yet others, less indebted or diseased, ensured that by judicious purchase their great houses would be admired by their peers and treasured by their descendants.

From A Strange Business: A Revolution in Art, Culture, and Commerce in 19th Century London by James Hamilton, published by Pegasus Books in September 2015. Reproduced by permission.