I am developing my capacity for writing genius.

Every day I concentrate my attention on becoming.

Becoming a better rounded artist—Crafter.

—Octavia E. Butler, note to self, 1971

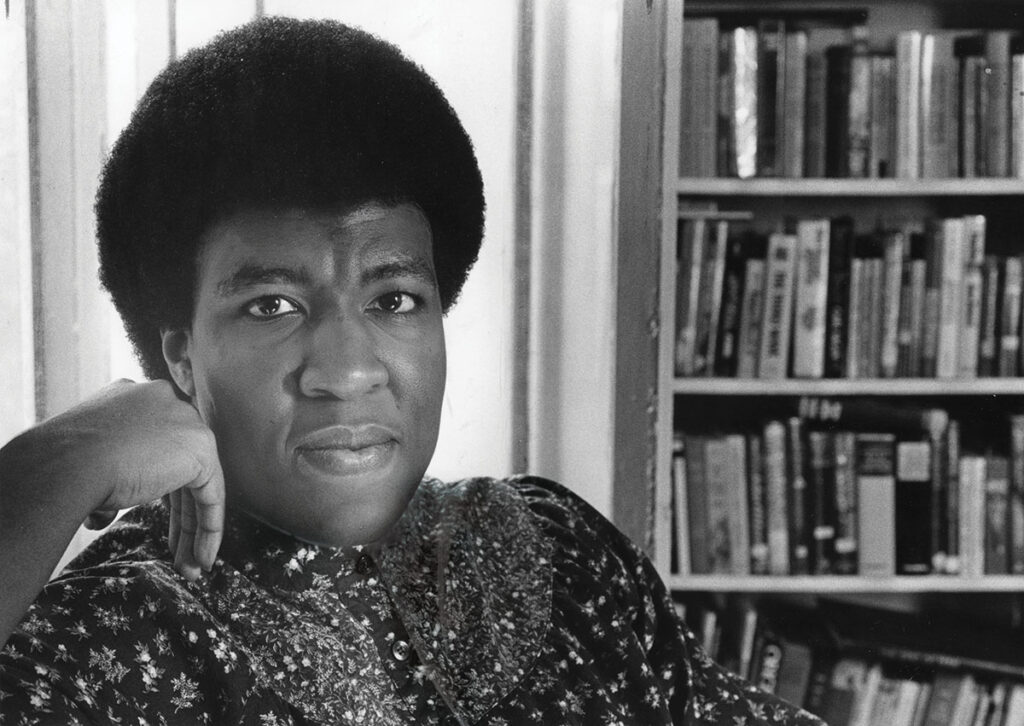

In a TV time-capsule moment from the dawn of the new century, an earnest Octavia E. Butler sits across from PBS’s Charlie Rose at his famous round table. She is serious, poised, dressed in a black turtleneck, her short Afro salted with gray, ready to talk about her writing life and the success of her most recent novel, The Parable of the Talents. Rose, in his typical cavalier style, tosses off a provocative question less than a minute into the interview: “Are you surprised you became a writer?”

“Oh, no,” Butler says, no pause. Declarative. “I think I had one choice—well, two choices. I could become a writer, or I could die really young. Because there wasn’t anything else that I wanted.” She is not smiling; her voice is deep, deliberate. She wants Rose to understand the gravity of her answer, the profound weight of this predicament.

By the time I happened upon this clip in 2015, nearly a decade after Butler’s death at 58, I had spent months deep inside the author’s remarkable archive at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, piecing together an essay that was part posthumous “interview,” part excavation of a writer’s life. I knew that the woman across the table from Rose was an invention; a vessel, if you will—Butler’s lifeboat for survival. For most of her life, her close friends and family often referred to her by her middle name, Estelle. But young Estelle dreamed of becoming a writer, and sketching that figure into vivid existence took practice and a plan.

As a Black woman writing stories that often defied strict categorization, Butler shattered many expectations and barriers, becoming the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. She was also the first Black woman to be awarded multiple Nebula and Hugo prizes. The author of more than a dozen books, including Kindred, Wild Seed, and Parable of the Sower, she wrote about a variety of subjects: “Some topics (themes) I’ve found myself returning to again and again,” she once cataloged in preparation for a talk. “Personal responsibility, power, community, biological and social change and individual isolation, aloneness and alienation.”

There is a keen dissonance between the indelible persona of strength and assuredness that Octavia outwardly presented and the shy, uncertain Estelle who attempted to face her fears in the pages of her diaries. Butler’s output—not just her mountain of chapter drafts, character studies, and tireless research, but also her daily journaling, meticulous scheduling, and self-penned affirmations—tells us that the work of self-construction and imagining herself a writer was as essential as time spent fine-tuning her actual writing, making the unbelievable believable.

Butler was a reader from a young age, but reading taught her only so much about the mechanics and flow of stories. There was a business end to learn as well. She acquired that knowledge with equal parts persistence, focus, faith, and serendipity, often on the fly and sometimes as the result of a misstep. (Her mother, who did domestic work for a living, once paid $61.20—more than a month’s rent—to a person posing as an agent; young Estelle had no idea that the agent-author relationship didn’t require such a transaction. She would not make that mistake again.) Her road to success, and her brutal honesty about its hindrances, reveals the risk and cost involved in carving out one’s own road as a writer. Her diaries, letters, and miscellaneous dashed drafts describe a difficult and uncertain journey—but also how she developed a system, a mindset, and a schedule, and made an oath not just to the page but to herself.

A lifelong writer myself, I deeply understand the benefits of passing along some of these hard-won lessons, especially the inside secrets you’re unlikely to learn without the advantage of goodhearted counselors or specific courses to steer you. Tracing Butler’s trajectory from a working-class Southern California home, where she was raised by a single mother, to a globally acclaimed author, I saw how powerful her story was. Poring over stacks of her well-purposed spiral notebooks, letters, diaries, quick notes-to-self, and affirmations, I understood the gamble she’d made to achieve her dreams—the cost to her personal life, her finances, her health. I filed away the tasks that made up her days, the effort she’d expended, the hope she’d invested. This single-minded pursuit allowed her to build an existence larger than the lives she saw around her. Loved ones told her that she should consider becoming a nurse, a teacher, or a government employee, something secure, with a good pension. She desired more, even if she couldn’t always fully visualize it. In short, just as she’d told Charlie Rose: writing saved her life.

“When I knew I wanted to be a writer, I wrote,” Butler set down in a 1993 journal entry. “I read, I sought information, criticism, publications. I worked at other jobs to get money. I did this for years, needing success, but not knowing that I could have it. I did it because I was driven by the need.”

There doesn’t seem a time when she wasn’t living inside words, whether between the covers of the secondhand books her mother would bring home for her or within the fantastical stories she made up herself. “I began writing at age 10 … unfinished horse stories and romances,” she wrote. “These were bits and pieces of novels.” The typewriter she received from her mother at the age of 11 made her dream feel tangible, if not yet attainable. By 13, she was completing “short stories that were actually truncated novels.”

Though learning to drive was a Southern California rite of passage for many youths, Butler had no license and instead traveled the LA basin by bus, which allowed her to read, write, eavesdrop, and daydream. It was on one of those buses that she found a discarded copy of The Writer magazine, a moment of pure kismet. “That copy told me there were potentially useful writer’s magazines available,” she later recalled, and she soon began formatting and sending her work to publications from “pulps to slicks.” In quick time, “I [started] getting them back by return postage,” she remembered, but she absorbed the sting, pressed forward.

Butler also made a safe space for herself in libraries—first the neighborhood branches within walking distance of her hometown, Pasadena, and then the large central libraries in downtown Los Angeles, a meandering bus ride away. These oases functioned as hideaway, office, or research center, where Butler spent time “bothering librarians,” as she would jest. Those librarians in turn pointed her toward books of varying subject matter—wildlife, the solar system, biology—as well as research strategies. Later, attempting to unlock the mysteries of what she termed “Bestsellerdom!”—what makes a book a “Big Book”—Butler checked out popular chart-toppers to better understand what publishers and readers were seeking. In her dime-store notebooks, she would write her own reviews of these titles to better understand their DNA—the books’ structure, pacing, character development.

Her tastes were omnivorous, her curiosity wide-ranging: astronomy, anthropology, science fiction, fantasy—all of it sparked her mind, opened fictional possibilities. Still, by the time she reached her 20s, her way forward remained unclear. She continued submitting her work, but to no avail. She enrolled at Pasadena City College and later Cal State Los Angeles, but thwarted by the lack of creative writing classes available, she ultimately dropped out. “Writing was the only thing I cared about,” she wrote in a 1977 autobiographical note, “so I left school to write.”

Determined to “make a way,” Butler signed on for all manner of part-time jobs: telemarketing, clerical temp work, toiling in a department store stockroom. She even worked for a time as a potato chip inspector. Yet even on the most demanding days, her body heavy with fatigue or doubt, she never put her writing on pause. She wove work around her writing windows, not the other way around, waking up by two, three, or four a.m., to spend time on the page—even if just to glare at it or wish for words to come—before readying herself for her pay-the-bills work. She’d plot out her plans in her journals and on wall calendars, charting not just time but also the number of pages she planned to complete (and then noting triumph when she succeeded).

She set to mastering her own mind: “I learn how to buckle down to get things done. … Budgeting time. Learning to make, not find, time,” she wrote. “Learning to establish priorities, budgeting money—how to get the best value out of a dollar, how to save.” To stay accountable, she would draw up contracts with herself in her own version of legalese. She would sign these with a flourish: “I will either finish 30 pages today, publishable on the special bond,” read one, “or I will not permit myself to stay home tomorrow. Contract OEB.”

Writer’s block would inevitably descend and linger. To push it back, she’d remind herself that “a blocked writer wants to care.” If she was running fallow, she would pluck inspiration from dependable sources; her diaries were seeds bursting with observations, character studies, emotional snags she was attempting to unknot. Obsessed with the news cycle, Butler was also an avid newspaper reader and NPR listener, plugging in to her transistor radio during her morning walks, homing in on headlines that troubled her or interview revelations that she found striking. Everything was fodder. Everything was a lesson, whether it was a shortcut discovered or a bad habit released and tossed away, such as the replacement of momentary self-doubt with assurances like, “We must become a writer—one who writes for a living as well as a way of life, one who sells regularly.”

Butler carried this ability to focus and persist for decades. Her dream came to fruition when she published her first book, Patternmaster, in 1976, but only when she published Kindred in 1979 did she become part of a larger national conversation, raising her profile beyond science-fiction circles. Kindred, like its author, refused narrow definition. Set in the antebellum South and infused with a supernatural element of time travel, the novel occupied its own genre: Butler herself categorized it not as science fiction but rather as “grim fantasy.” Though it wasn’t a blockbuster, Kindred appeared on Doubleday’s general fiction list, gaining Butler new readers and, more important, signaling that all those years protecting her voice, time, and vision had indeed paid off. All of the sacrifice, isolation, and rejection slips hadn’t simply toughened her up. They had given her a more assured sense of herself in the world. She was a writer.

And all this without a confidant to whom she could admit her insecurities (she’d vowed long before to “keep [her] own counsel”). She had to find a balance, to try to tame her perfectionism—to be her best, but to have self-compassion: “Stay with your goal. Don’t waver an inch from it. But don’t beat your head against the wall. If you’re not getting results, try a new approach. There is a solution. Start fresh. Even recreate.”

In one of her most frequently quoted essays, “Positive Obsession,” Butler writes about the laser-focused commitment to a dream: “Positive obsession is about not being able to stop just because you’re afraid and full of doubts. Positive obsession is dangerous. It’s about not being able to stop at all.” Her stow of messy, worried drafts, library call slips, intricate outlines, busy marginalia, queries, and diaries forms a monument to that single-mindedness that she describes so achingly. The physical archive of her writing life holds the precious blueprints to how she created both her work and, ultimately, a new self: no longer just Estelle but Octavia, the visionary we see bantering with Charlie Rose, the mentor penning encouraging letters to aspiring writers, the veteran writer, still worrying over the page because—as always—getting it right mattered.

She attested, time and again, that the act of writing wasn’t magic. It wasn’t waiting for the muse to descend. It was sitting down to face the page, face oneself, word by word, idea by idea, filling up the page, and then the next. “Forget luck, forget inspiration,” she wrote. “Habit. It’s habit that will sustain you. Persistence.” This quote echoes inside me when I’m tussling with my own work: turn the page, uncap the pen. Begin again.

I think often of her voice, that burnished, confident Octavia voice, and what she told Charlie Rose later in their interview: “You have to make your own worlds. You’ve got to write yourself in. Whether you are a part of the greater society or not, you’ve got to write yourself in.”

Although she might not have achieved that “Bestsellerdom!” goal in her lifetime, two of her novels and her collected short stories were recently published by the Library of America, a recognition of her importance to American letters and her endurance as an artist. Those daily affirmations of hers, the focused hours spent bent at the task, the words she sent out into the world—all of this cleared the way. She was always considering the shape of possibility, dreaming beyond what was tangible. She passed on this practice to other writers, those of us toiling alone, at the edges, in the dark—mirrors of herself. In 2020, when one of her best-known novels, Parable of the Sower, landed on The New York Times bestseller list, 14 years after her death, nearly 30 years after its publication, I heard Butler’s words echoing again, now an elegant coda: “Stay with your goal. Don’t waver an inch from it.” Her win was ours, too.