The many lives of Samuel Steward defy expectations: English professor, novelist, tattoo artist of choice for the Hells Angels, gay erotica writer, avid documentarian of his sexual adventures, Kinsey collaborator, and … monthly columnist for the Illinois Dental Journal. Under the pseudonym Philip Sparrow, Steward wrote dozens of essays at the behest of his personal dentist, who happened to be the magazine’s editor at the time. “While I was at his mercy in the chair one day in 1943,” Steward recalled later, “he talked me into starting a series of articles.” Although the original premise of the column was to show dentistry from the perspective of the patient, Steward’s columns soon veered off into wild, delightfully eclectic directions.

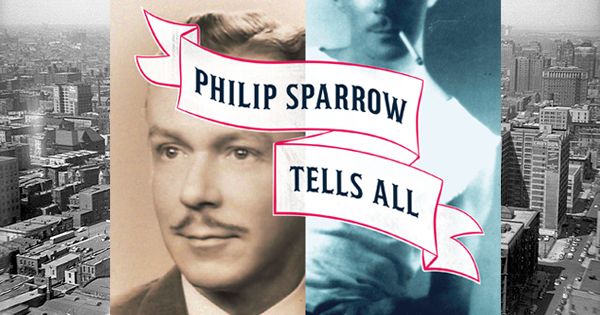

For five years, he covered everything from cryptography, pet cemeteries, medieval recipes, bodybuilding, and opera to his own friendships with Gertrude Stein, André Gide, and Thornton Wilder, along with allusions to his dalliances with ballet, ballet dancers, and Rock Hudson—all in a trade magazine for Midwestern dentists. Read the opening from his November 1944 column on Alcoholics Anonymous, of which Steward himself was a member, from Philip Sparrow Tells All: Lost Essays by Samuel Steward, Writer, Professor, Tattoo Artist.

Tradition hath it that there are six stages in getting drunk: jocose, amorous, bellicose, morose, lachrymose, and comatose. Almost anyone can endure the happy bibbler, to whom the world is bright and every man a friend; and the amorous one can usually be kept in control with a few simple holds of jiujitsu tactfully employed. The belligerents are somewhat worse to handle, the lachrymose and morose a trial more often than not, and the comatose—well, they’re a vegetable grater on everyone’s nerves and patience.

Your feathered friend has for some time known one of the greater and better drunks of this area, a fellow who wondrously combined the last four stages. Like Housman’s Shropshire lad, many’s the time that down in lovely muck he’d lain, happy till he rose again; and frequently you could find him in the gutter, casting a lacklustre eye up at the Big Dipper, and inquiring of the chance pigeons passing on the curb if there were any messages for him from home. Fifteen years is a long time, and at the rate of more than a quart a day, he must have consumed a helluva lot of booze. From simple and childlike beginnings—such as the rotgut and needled near-beer of prohibition days—he progressed rapidly, until some few years ago certain subtle changes began to appear. The appetite vanished, the nights were sleepless, the temper quickened and the mind slowed down, the will weakened and the fingers shook. The agreeable opalescent fogs through which he had viewed the world swirled and darkened into damp mists and swamp miasmas. From the status of a controlled drinker, who merely looked forward to the usual weekend punctuation of his daily routine with a mild orgy, he stepped across the line into the dim and shuddery region of alcoholism. The morning eyeopener became a dreadful necessity, even when he had to loop a towel around his neck and draw the glass up to drink; he measured the day by counting the time between snorts and the distance between taverns. In short, he experienced all of the symptoms so brilliantly described by Charles Jackson in his recent novel, The Lost Weekend.

We ran into each other not long ago, our paths not having crossed for a coupla years; and as we strolled down the street, my steps quite naturally turned into the nearest bar—and he followed. “Double bourbon—neat,” I said; “Ginger ale,” said he. I goggled at hearing that; it was as if Superman had asked for a pair of knitting needles.

Reprinted with permission from Philip Sparrow Tells All: Lost Essays by Samuel Steward, Writer, Professor, Tattoo Artist, edited by Jeremy Mulderig, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2016 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.