Red: The History of a Color

Read an excerpt from Michel Pastoureau’s new book about the color of love and rage

What’s in a color? There’s the physiological way in which we experience it, via light refracting through our retinas. And then there are our emotional responses to color: blue to calm, red to excite, yellow to sell magazines (truly). Scientific research and empirical studies back up what we know about color, and how we respond to it. But the question of what color was to ancient cultures, to our ancestors, to prelinguistic society—this requires a deep understanding of how color seeped into language and society, as Michel Pastoureau demonstrates in his new book, Red: The History of Color. And as it turns out, our modern conception of color is strikingly different from our forebears’.

For the Greeks and Romans, red was the first color, the color par excellence. And yet, can we say it was the favorite color? Probably not. It is not that red was not admired, sought-after, and celebrated, but the very notion of preference implies an abstraction, a conceptualization of color that antiquity hardly experienced. To say “I like red; I don’t like blue” presents no difficulty today, in English or in French or any other European language. Color terms are not only adjectives; they are also nouns that designate categories of color in the absolute, as if it were a matter of ideas or concepts. In antiquity, that was not the case. Color was not a thing in and of itself, an autonomous abstraction. It was always linked to an object, a natural element, or a living being that it described, characterized, or individualized. A Roman could perfectly well say, “I like red togas; I hate blue flowers,” but it was hard for him to declare, “I like red; I hate blue,” without specifying something in particular. And for a Greek, Egyptian, or Israelite, it was even more difficult.

In what period does the change occur—that is, the shift from color matter to color concept? It is a difficult question to answer, because the evolution took place so slowly and according to different rhythms for different areas. But it does seem as though the early Middle Ages played a decisive role here, especially with regard to language and lexicon. Among the Church Fathers, for example, color terms were not only adjectives but also nouns. Of course we already encounter colors as nouns in classical Latin, but not frequently and more in connection to the figurative meaning than the actual chromatic meaning of a color. For certain Church Fathers, that was no longer the case; nouns spoke directly of the color. They might be actual common nouns, like rubor or viriditas, or adjectives in the neuter form and nominalized (rubrum, viride, nigrum): proof that color had lost its materiality and had begun to be considered a thing in and of itself.1

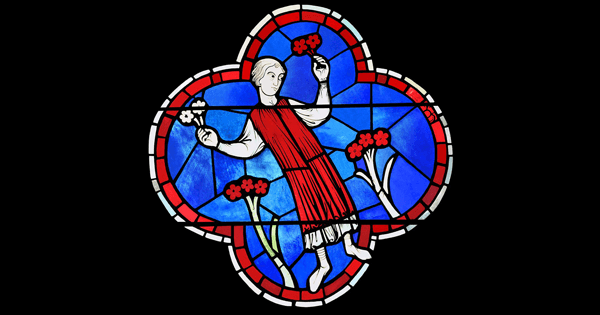

In the twelfth century, when first the system of liturgical colors and then the earliest coats of arms and the language of heraldry spread throughout the West, the matter seemed settled. Henceforth colors could be considered as abstract, general categories. Freed from all materiality, red, green, blue, and yellow were conceived in the absolute somehow, independent from their supports, their brightness, shade, pigments, or colorants. Among those colors now appreciated for themselves, red was the favorite.

Excerpted from Red: The History of a Color by Michel Pastoureau. Published by Princeton University Press.