In 1849, Seminole chief Coacoochee (“Wild Cat”) left Florida to explore Texas and the southern Plains in search of new territory. Eventually, he led his people to northern Mexico, where he worked for the Mexican government as an explorer in exchange for land—as part of a broader mission to seek out and fight the Comanches and Apaches living along the U.S.-Mexico border.

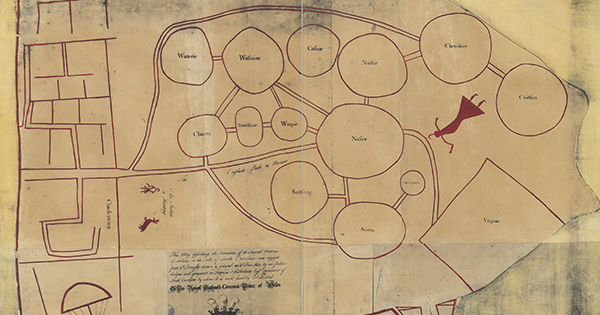

Coacoochee’s story will be part of a book by Cameron Strang, a historian at the University of Nevada–Reno: the first study of Native American explorers of the western United States. “I’m interested in how they generated knowledge in the West and reported the information back to the East,” says Strang. It’s possible that during his explorations, Coacoochee conceived of geographical space in a manner reminiscent of the Southeastern Native American “circle-line maps,” which render space as adjacent circles representing alliances among social groups—these relationships being more important than topographical details. “Coacoochee consistently emphasized geopolitical relationships and alliance networks during his explorations,” Strang says. Drawing on oral and written records, Strang sees the work of eastern Native Americans “who explored the trans-Mississippi West as a creative response to European and U.S. imperialism.”

As Coacoochee’s experience in Mexico shows, Native American exploration had a darker side. The U.S. Army often hired Delaware Indians as scouts throughout the Plains. As auxiliaries to the U.S. Army, they sometimes assisted in the conquest of other Native Americans.