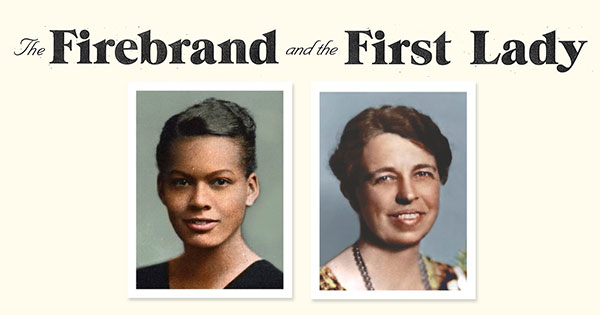

The Firebrand and the First Lady

Read an excerpt from Patricia Bell-Scott’s book about Eleanor Roosevelt and Pauli Murray

You may not have heard of Pauli Murray—poet, lawyer, activist, first African-American female Episcopal priest—but her impact on the Civil Rights Movement was profound. Thurgood Marshall anointed her compilation of all the race laws in 1950s America, States’ Laws on Race and Color, “the Bible for civil rights lawyers,” and then used it for the NAACP’s strategy in Brown v. Board of Education. Ruth Bader Ginsburg leaned on Murray’s legal arguments—and even named her as a co-author of the brief—in one of the landmark cases of her career, Reed v. Reed, which in 1971 was the first application of the Equal Protection Clause to a case of sex discrimination. And in the late 1960s, Murray co-founded the National Organization for Women and fought to keep gender as one of the protected categories of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

But before all that, Pauli Murray was a young writer incensed by a speech that President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—where Murray was denied graduate admission because she was black—praising the school for its commitment to social progress. She wrote a letter to the White House, and Eleanor Roosevelt responded with a short note: “I understand perfectly, but great changes come slowly … The South is changing, but don’t push too fast.”

After FDR passed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the internment of Japanese Americans, Murray sent another letter to the White House. This time, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote back at length, initiating a correspondence—and friendship—that would go on for decades. Their friendship is the subject of a new book by Patricia Bell-Scott, The Firebrand and the First Lady. Read her account account of the letter that led to Murray and Roosevelt’s first conversation and inspiring friendship.

“As President of a nation at war,” Murray [wrote in her letter], “you have almost unlimited emergency powers. . . . If Japanese Americans can be evacuated to prevent violence being perpetrated upon them by our less disciplined American citizens, then certainly you have the power to evacuate Negro citizens from ‘lynching’ areas in the South, and particularly in the poll tax states.” …

Murray was not sure that her letter would reach the president’s desk or if it would move him. So she sent it to Eleanor Roosevelt with a cover note: “Will you read this letter and pass it on to the President? I only made one copy and did not want this one to get lost in a maize [sic] of secretariats. If there ever were a Woman’s Revolution, I’m afraid you’d have to run for President.” As justification for the tone of her missive to FDR, Murray added, “If some of our statements are bitter these days, you must remember that truth is our only sword.”

Although Murray’s intent was to rouse the president, her proposal—that the government evacuate African Americans from the South as it had done on the West Coast with Japanese Americans—angered Eleanor Roosevelt. The first lady’s indignation was rooted in her opposition to internment and her inability to persuade the administration that the policy was unjust. “If we can not meet the challenge of fairness to our citizens of every nationality . . . regardless of race, creed or color; if we can not keep in check anti-semitism, anti-racial feelings as well as anti-religious feelings” she had argued, “we shall have removed from the world, the one real hope for the future on which all humanity must now rely.” As FDR and his advisors moved forward with the evacuation program, Eleanor Roosevelt implored, “These people are good Americans and have the right to live as anyone else.” Despite her entreaty, the president issued his directive on February 19, 1942.

While the first lady did not publicly criticize the internment program after the executive order was issued, knowing that there were “children behind barbed wire looking out at a free world” pained her. She worked diligently to prevent ill treatment in the camps, separation of families, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. In no mood for Murray’s sarcastic “outburst,” Eleanor Roosevelt penned her sharpest letter to date.

Excerpted from The Firebrand and the First Lady by Patricia Bell-Scott. Copyright © 2016 by Patricia Bell-Scott. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.