The Meaning of the Library

A brief excerpt from a new collection of essays, edited by Alice Crawford

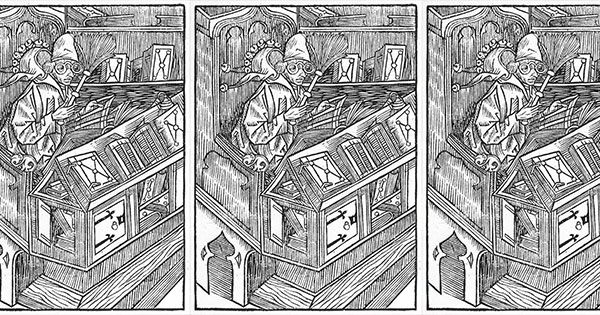

Libraries may be hallowed repositories of scholarship and erudition, but ever since Aristotle first began amassing papyrus scrolls, they have also been comic places. They have always been “inhabited by cerebral individuals who seem inherently funny to ordinary people of common sense,” as Edith Hall writes in The Meaning of the Library, a new collection of essays by a variety of writers. Hall’s piece opens with an extended joke Aristophanes made about Euripides’s library, and humorous revelations crop up throughout the book: the first public library was founded by a despot, building a library in the Renaissance lost its allure once everyone could do it, some of the most extensive personal libraries in the Victorian era were filled with pornography and gruesome penny dreadfuls …

Though the advent of the search engine seems to be the most potent threat to the long history of the library, this collection illustrates that libraries, both public and private, have “constantly been built up with gusto, destroyed by malice or neglect, then rebuilt by a hopeful new generation,” as editor Alice Crawford writes in the introduction. In the spirit of sharing the love of books, as all libraries do, here is an excerpt from John Sutherland’s essay, “Literature and the Library in the Nineteenth Century,” which shows just how much gusto books can inspire:

How important are books to those truly in love with them? Rick Gekoski opens his bibliomemoir, Outside of a Dog (2011), with the teasing suggestion that if his wife fell out one side of the lifeboat and his books out of the other side, the true bibliophile would be strongly inclined (so long as no one was looking) to rescue the books first.

Harry Elkins Widener, legend has it, was drowned on the Titanic because he insisted on rushing back to his state room for his treasured volume of Bacon’s Essays. “Women, rare books, first-class passengers, and children first!” the young bibliophile might have bawled, had he made it back to the first-class deck. One of the world’s great libraries—the Widener at Harvard—commemorates Harry’s fatal love.

Trollope tells us in his Autobiography that, having recently been obliged on doctor’s orders to give up hunting, his one consolation in life was his library:

I own about five thousand volumes and they are dearer to me even than the horses, which are going, or than the wine in my cellar, which is very apt to go, and upon which I also pride myself.

The Chronicler of Barsetshire gallantly refrains from putting a valuation on Mrs. Trollope. One hopes she would, at least, outrank the horses.

Reprinted with permission from The Meaning of the Library: A Cultural History, edited by Alice Crawford, published by Princeton University Press. © 2015 by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved.