This week, Smarty Pants host and Scholar senior editor Stephanie Bastek delves into the history of Black Studies at her alma mater, Reed College, drawing connections between the fight for a Black Studies program in 1968 and the efforts of Reedies Against Racism to diversify the college’s mandatory freshman humanities course 48 years later. Speaking with former students and members of Reed’s Black Student Union, Bastek recounts the 1968 BSU occupation of Eliot Hall, one of the largest buildings on campus, as part of the campaign for a Black Studies program. The program was established, but not without backlash—and rifts among faculty members would threaten Reed’s foundation for decades to come.

- Read Martin White’s essay, “The Black Studies Controversy at Reed College, 1968–1970” in the Oregon Historical Quarterly

- In Memoriam: Linda Gordon Howard, Calvin Freeman, José Brown

- All images below taken by Stephen Robinson, and courtesy of the Reed College Library

Featured voices in this episode: Andre Wooten, Mary Frankie McFarland Forte, Martin White, Stephen Robinson, Roger Porter, George Brandon, Steve Engel, and Suzanne Snively. Ron Herndon oral history audio courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society. Archival recording of the October 28, 1968 BSU town hall featuring Cathy Allen and Ron Herndon courtesy of the Reed College Library.

Produced and hosted by Stephanie Bastek. Original music by Rhae Royal. Audio storytelling consulting by Mickey Capper.

Listen to all five episodes of Exploding the Canon:

Subscribe: iTunes/Apple • Amazon • Google • Acast • Pandora • RSS Feed

Download the audio here (right click to “save link as …”)

Transcript:

The year 1968 is remembered as tumultuous for many reasons: the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the wave of student demonstrations from Paris to Berlin, the My Lai massacre, and heightened anti-Vietnam War protests across the country, including college campuses.

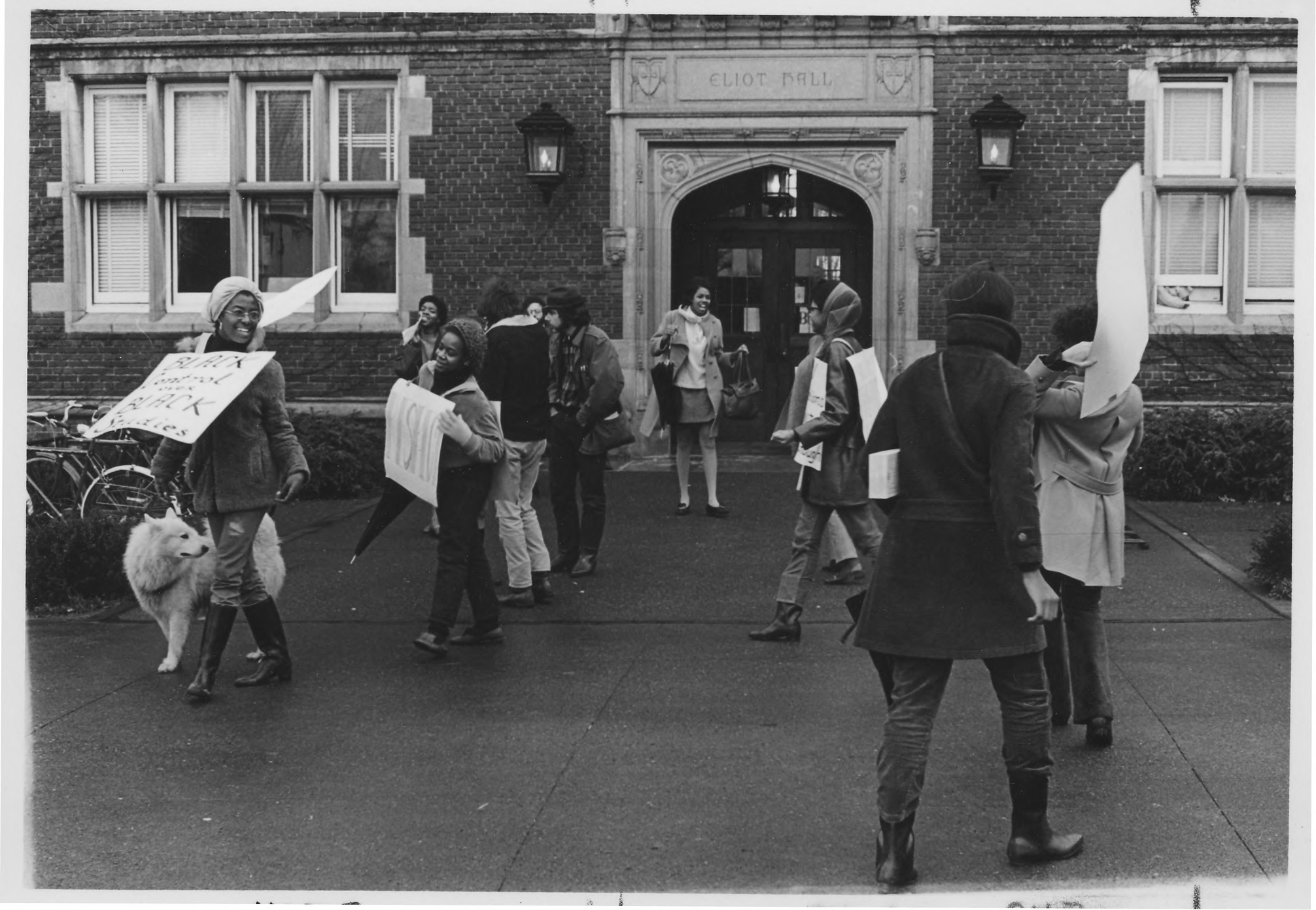

1968 was a big year at Reed College, too: in its demand for a Black Studies Program, the Black Student Union took over one of the largest buildings on campus: Eliot Hall. Andre Wooten was a junior and the vice-president of the BSU:

ANDRE WOOTEN: I was one of the guys who locked themselves up in the building, seven of us really, we locked ourselves up in the president’s office and kept anybody from getting in there for a week.

Mary Frankie McFarland Forte was a sophomore and the secretary of the BSU.

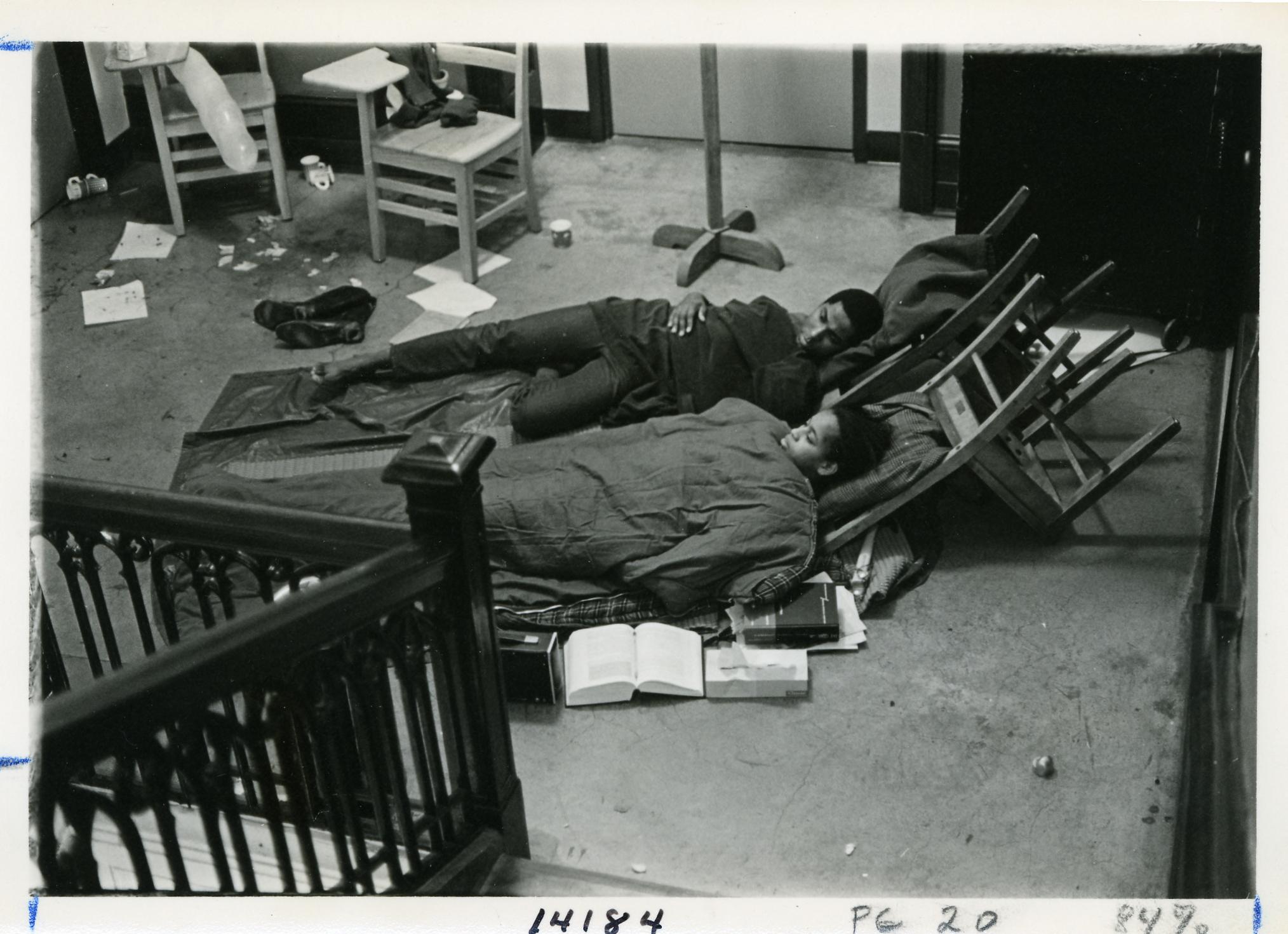

MARY FRANKIE MCFARLAND FORTE: I was sleeping in a sleeping bag on the floor with José Brown. He was in the next dorm; he would come over—“Mary, come on, let’s go down.” And we had our sleeping bags, and we slept. I do remember the floor being a little hard too.

****

Exploding the Canon examines the 2016-2017 struggle to change the mandatory freshman humanities course at Reed College, and how far that reckoning with racism and Eurocentrism really went. What does the fight for Black Studies in 1968 have to do with the struggles of Reedies Against Racism years later? Well, Reed College is a majority-white school in a majority-white city in a majority-white state. In fact, while Oregon was still a territory, it passed laws excluding Black people.

Until 1964, only two Black students had ever graduated from Reed. But starting in 1964, the school was one of seven private colleges to receive a $250,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to establish merit scholarships for Black students. Martin White, who graduated from Reed in 1969, published an extensive article in the Oregon Historical Quarterly in 2017 about the events of 1968:

MARTIN WHITE: The original grant was for three years, and then it was extended for another three years. So every year they were bringing in 10 or 15 Black, new Black freshmen.

By 1968, there were 35 Black students at Reed. But for scholarship students like Stephen Robinson, who came from a public high school in Newark, New Jersey …

STEPHEN ROBINSON: Oh, it was pitiful. It was extraordinarily non-diverse. In fact, I think at the time there may have been 1100 students total, and out of that there may have been 30 or 40 Black students.

Mary, who also went by her middle name Frankie in college, was another full scholarship recipient. She came from a public high school in Oakland, California.

MARY FRANKIE MCFARLAND FORTE: All those classes, I had to be the only Black in there. My freshman roommate, she was from Medford, Oregon. She had never met a Black person.

****

The Black Student Union had formed in 1967. Ron Herndon was a master’s student at the time. The Oregon Historical Society conducted a 1988 oral history with him:

RON HERNDON: I was looking forward to having a place where I could do nothing but learn. I came out here, to Reed College and found that it was just as racist as any institution I had encountered in my previous 23 years. No Black books, no Black classes. So I got involved with Black Student Union and we demanded that they set up a Black studies program. They balked.

In the fall of 1968, the Black Student Union had coalesced around that demand for a Black Studies program, with Black studies courses taught by Black professors. At that time, there was only one African-American professor—Michael Harper, who was poet in residence at nearby Lewis & Clark College and taught only part-time at Reed in the Literature department.

MARY FRANKIE MCFARLAND FORTE: It would’ve been nice to have a Black teacher that we could talk to. The only Black people that worked at the school at the time, they either were cooks in the commons or they were cleaning the dormitories. And other than that, you didn’t see Black people.

STEPHEN ROBINSON: I think it was Ronnie Herndon at the time who said, we’re not being given the tools to affect the kind of change that’s necessary in our communities when we return. You know, you could look at being trained to be a very efficient cog in a bigger machine, or are you going to be given the tools to dismantle the machine?

For a while, it seemed like the BSU was on a course to victory that fall. Martin found a lot of material in the archives for his article on the fight for Black Studies:

MARTIN WHITE: They began by presenting their demands to the faculty. And the faculty appointed a committee to help with the process of creating a Black Studies program. I think there was a period there in the fall of 1968 where things were moving along. And then after Thanksgiving break, the situation changed. And according to what both people on the faculty and Black students have said, some of the Black students went to Washington DC where they met with other Black students from other colleges. And as a result of those meetings in Washington DC, they came to the conclusion that control over hiring and firing faculty was essential, that they couldn’t just have a program and have the all-white faculty at Reed College controlling who was hired and fired.

The demands were typewritten and presented to the faculty on November 22. In all capitals, it read:

REED IS ACTIVELY RECRUITING BLACK STUDENTS. THEY BRING US HERE, FORCE US TO STUDY THE CULTURE OF OUR OPPRESSORS (EUROPE AND AMERICA), AND THEN NEGLECT OUR OWN CONTRIBUTIONS TO CIVILIZATION.

Their demands were for a commitment from Reed to establish a Black Studies program in some form, for Reed to hire Black consultants to confer with the BSU on creating it, and for the faculty to cede absolute control of selection for this future Black faculty to the BSU. And, until enough Black professors were hired, the BSU wanted control of the curriculum, and veto power over any courses dealing with people of African descent—like the only two then currently being taught at Reed. Faculty minutes record the BSU’s reason for this demand:

STEPHEN ROBINSON: “Being black is an essential condition to understanding fully black people’s needs. You do not know how you are uneducated in this area and are thus not qualified to set up a program to educate yourselves or others.”

MARTIN WHITE: The first two demands just had to do with creating a program and bringing in consultants to help get it set up. And really there was pretty broad support among the faculty and the students. Had it just been the first two demands, it would’ve sailed through much more easily. But the last three demands were a sticking point and a lot of faculty members just could not get past those, even if they were favorably inclined towards Reed creating a Black Studies program.

The faculty responded three days later, completely ignoring the last three demands. Roger Porter was one of the Young Turks who supported the BSU:

ROGER PORTER: My gut feeling is that there was something insular about the faculty. The allegiance to Reed, the sense that Reed was such a special place, was so fragile and so delicate, and that the faculty had to be, uh, careful guardians of the traditions of the institution. And it made for what I thought was a kind of claustrophobic atmosphere. Uh, the word that kept being brooded about a lot was the mission of the college, which always made me feel that, if colleges have missions in that sense, it’s easy to assume there are heresies that the missions protect against.

The older, more conservative camp of faculty were those who had survived the McCarthy era. These faculty members were committed to maintaining a strong degree of academic freedom and control over hiring and firing.

MARTIN WHITE: The older faculty found that the younger faculty members were much more sympathetic to student demands about a whole array of things than they themselves were. And the younger faculty also did not have this institutional memory about the challenges that Reed had faced in the fifties, where the House Un-American Activities Committee targeted Reed College because they thought it was harboring communists. And so they sent a bunch of congressmen and staff members and held hearings and ran a bunch of faculty members over the fire. And it ended up that two faculty members were fired from the college for either belonging to the Communist Party or not revealing whether they did or not, and a staff member as well. So three people left, and as a result of that, the president of the college had to resign early and the faculty felt very strongly about any kind of invasion of their rights to hire and fire faculty members or set the curriculum.

The BSU got the sense that the faculty did not share their sense of urgency. Andre Wooten, who was its vice president, reflected on this later.

ANDRE WOOTEN: We didn’t feel that our requests and/or demands were being taken seriously. There was a definite faculty opposition because back in those days, even some of the history professors were saying, there is no serious reason to study African history. There’s nothing there. And it was all just because they were ignorant. They thought everybody else was ignorant and should continue to be ignorant. But if you begin digging up the books and the old rocks, you find that … British historians were writing that Egypt was the light of the world back in the early 1800s.

Something had to change.

ANDRE WOOTEN: We realized that a lot of historical movements have been taken by people taking direct action. And so it was determined that we would take over the admin building at starting about three o’clock one morning, and seven of us showed up and did that.

That was the morning of Wednesday, December 11, 1968. Linda Gordon Howard—whose name we heard earlier as the founder of Renn Fayre—had woken up early to slip small pieces of paper into every student mail box, reading simply, “The Black Student Union of Reed College has taken over the second floor of Eliot Hall.”

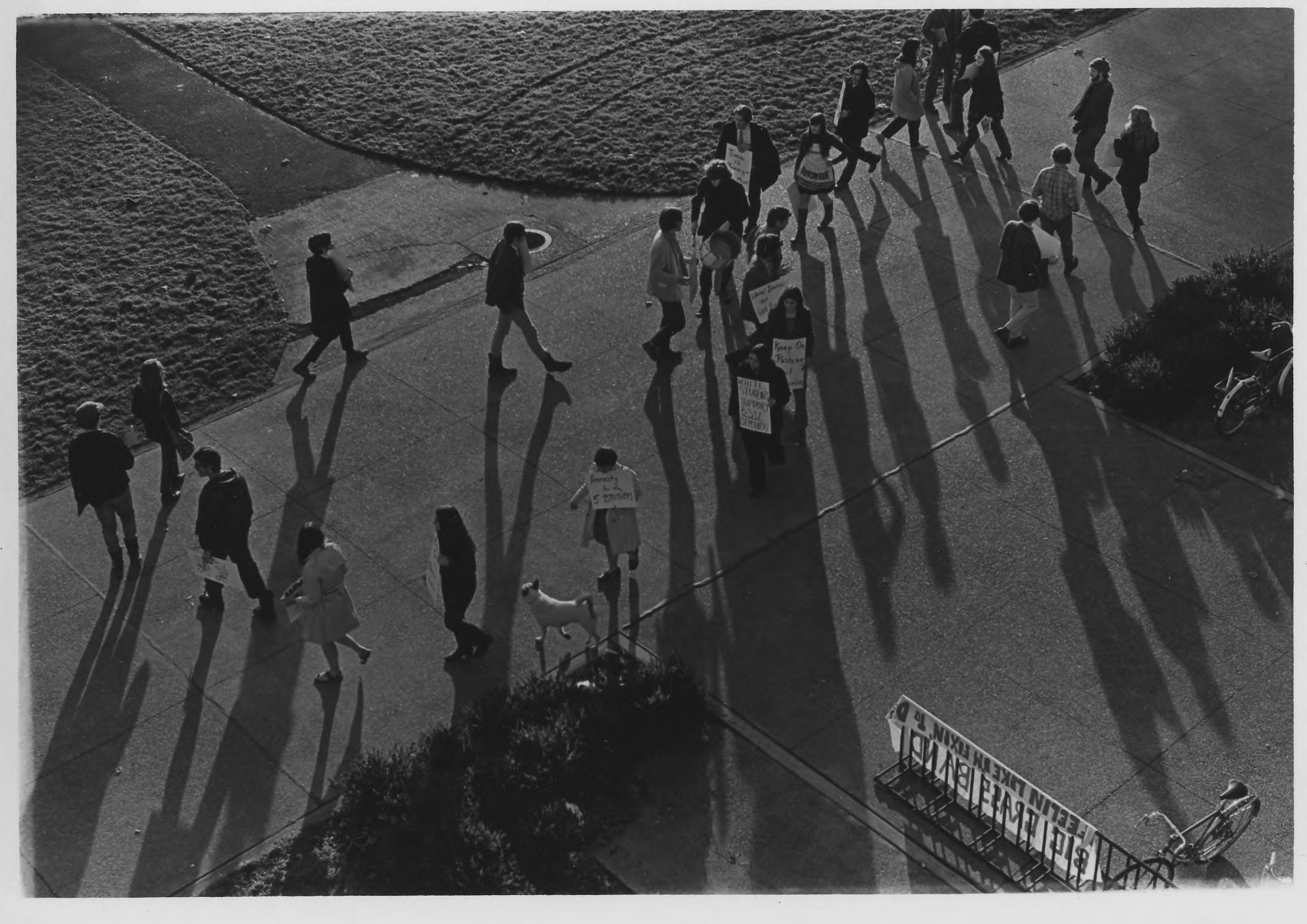

MARTIN WHITE: I was in a class and a group of Black students appeared in the hallway. They had waste baskets that they turned into drums, and they were banging on those and asking everybody to leave their classes to support the occupation, which they were beginning of Eliot Hall.

Four or five students had locked themselves into President Victor Rosenblum’s office on the second floor, armed only with a box of groceries. Everyone else stayed in the main hallway, where they blocked access to the admission office, registrar, and finance office—oh, and faculty mailboxes.

ANDRE WOOTEN: We wanted to make them a little more uncomfortable and kind of try to get them to understand how uncomfortable we felt in this bastion of privilege.

They sat and held their ground for the whole day. Then they pulled out their sleeping bags and stayed overnight into the next day. And the next day. George Brandon recalled a sense of exhilaration, but also the boredom:

GEORGE BRANDON: Once you’re there, it is just what are you going to do with your time? It wasn’t like there was any active attempt to really barge in and force us out. That didn’t happen. You get messages, people let you know what’s going on on the outside while you’re there. Most of the time you’re just sitting there. You’re just sitting there and you read something. You have some food, talk about who else is in there about the meaning of what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and wondering what’s going on outside of the hall. But inside it was fairly peaceful actually.

The students occupied the building in shifts, and the BSU got a lot of support from white students on the outside, some of whom heeded the call for a boycott of classes. Steve Engel had been involved with protests against the Vietnam War on campus, and he was friends with a lot of the Black students in the union.

STEVE ENGEL: I thought that it was gutsy, and I thought that it was making a statement we could hardly make by going rah rah outside. And I knew they were taking chance. I knew they were putting themselves on the line, and I think that was a big piece of the motivation. All right, we’re not going to let them get cut off here, let’s do what we could. Bring food, make something of a to do so that it would be clear that it was not just Black students alone in the building.

Hand-written leaflets from the Reed Boycott Committee announced: “One week to White Christmas. No white studies until black studies! BOYCOTT … If you support the BSU, strike. Spend your time talking to your professors explaining why the BSU proposals must be accepted.” Martin White remembers a flurry of other publications, special editions of The Quest, pickets, rallies.

MARTIN WHITE: This was a week or 10 days before Christmas break, the whole rest of that term was given over to political action.

The business of the college was totally interrupted:

MARTIN WHITE: The college could no longer issue checks to faculty members or to student workers. So it was a very intense situation and it was hard to say how it was going to work out.

Meanwhile, the Black students inside Eliot Hall were getting nervous.

ANDRE WOOTEN: I swore I would never lock myself inside of anything ever again in my life. It was just crazy. It felt like a sitting duck. I mean, there were police cars driving around. They never came in and stormed us, but it was a very nervous time.

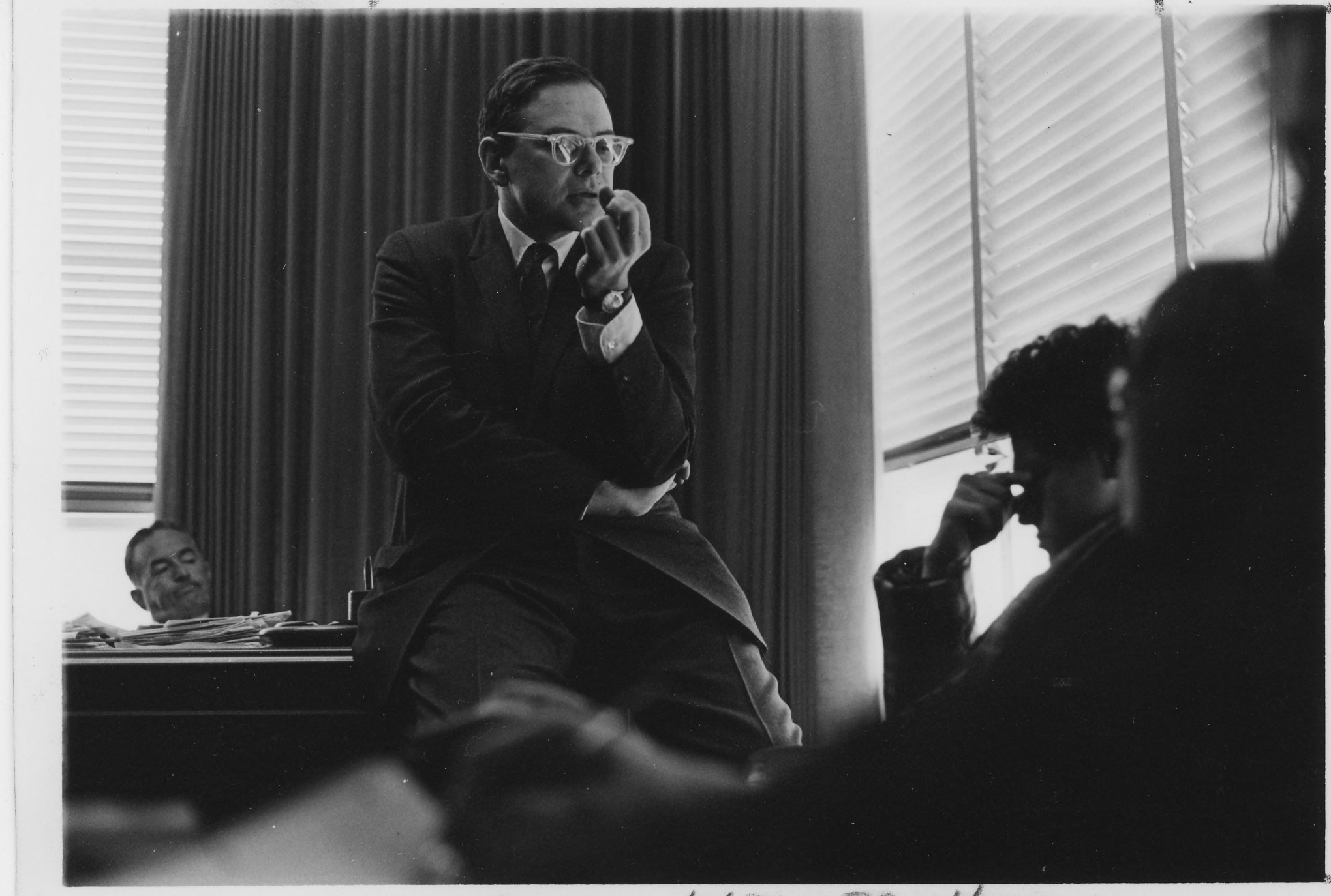

President Rosenblum never did call in the police, though a few faculty members desperately wanted him to. At 3 PM on the first day of the occupation, Rosenblum called for a closed meeting of the faculty, after which they released a resolution rejecting the demands for student control over the hiring and firing of Black Studies professors, but supporting “in principle” the creation of a Black Studies program.

MARTIN WHITE: President Rosenblum was, I think very skillful in managing, speaking to the Black students, speaking to the faculty, trying to get people together to talk. And the Black students also I think were very disciplined. There was no resort to police violence on the Reed campus, which was not a usual thing. These protests were going protests against the war, protests about the state of higher education. Students were in an uproar all over the country and in places like San Francisco where this process was going on at the same time at San Francisco State, there was a huge police action led by the president of the college who got a baton out and started whacking kids in the head. So very different at Reed, which was, I think everybody should be applauded for that.

Suzanne Snively, a white student who was good friends with Mary Frankie McFarland Forte, happened to be studying constitutional law with President Rosenblum:

SUZANNE SNIVELY: Of course, he gave me the impression that he was succeeding with the traditionalists, and I was impressed with his approach that he insisted on this being a Reed discussion and not bringing in the police, enabling the Black students to assert a bit of power in order to draw attention to their case.

On Thursday, the faculty held another meeting, this one open, and the contentiousness of the debate was as much of a disruption to the college as the occupation itself. As emeritus economics professor Carl Stevens, also from the Reed class of 1942, told Todd Schwartz for a 2003 edition of Reed Magazine: “I remember one colleague shouting about how he would take the college out of his will … I was astonished at how fragile some of my colleagues thought Reed was. That merely having a black studies center would somehow damage the entire education program.”

Further negotiations between a few BSU and faculty representatives resulted in a new proposal, brought to a December 17 meeting of the faculty by the BSU, for an autonomous Black Studies Center, whose director and faculty would only answer to the president and trustees—not the faculty. We only have print records of this, but I asked a colleague to re-enact them.

The Faculty supports in principle the establishment of an autonomous Black Studies Center under the auspices of the Reed Institute. It is understood that the Center would subscribe to the standards of academic freedom … It is understood that the Black Student Union and consultants will assist in naming the first director.

The Eliot Hall occupation was entering its sixth day. Meanwhile, Linda Gordon Howard had just been elected vice president of the student body—an election she’d totally forgotten about from inside her sleeping bag in Eliot Hall. She resolved to get the rest of the faculty on board with the compromise proposal as quickly as possible. Since her freshman year, she had spent a lot of her spare time in German professor Ottomar Rudolph’s office, listening to him gossip about his colleagues. This was her secret weapon: she knew where all the faculty fell along political lines. “All we have to do is manage these people,” she told me later, as she set up two-on-two conversations between BSU members and professors, beginning with the most sympathetic.

They worked their way, two-by-two, through all the faculty, until they hit 51% in support. It’s something she regrets, she told me: “What I did was vote-counting. My mistake was stopping at 51%. It wins an election but it’s not a mandate.”

In his article, Martin White points out that the faculty at the time “was not merely a white male patriarchy in theory but in actual fact.” There were no full-time Black professors, and only a handful of minority faculty . Just 12 percent—18 out of 146 people—were women.

Roger Porter remembers the vote that followed the night of Wednesday, December 18:

ROGER PORTER: The vote was enormously close. I think it passed by two or three votes. Uh, and the conservative—let’s called them conservative—faculty around that issue made sure that emeritus faculty came to the faculty meeting in which that decision was made. Normally, emeritus faculty never come to meetings. And I mean, there were people in wheelchairs. I think there was one guy in a stretcher. I mean, it was really a bizarre scene. And of course, they all voted conservatively, but it passed. And were people who wept at that meeting and said it’s the darkest day in the history of Reed College.

In the minutes, 22 faculty members insisted on going on the record in opposition, something only done in faculty meetings by request. Only four wanted to be on the record in favor, including Roger Porter. The resolution passed 53 to 50: there would be a Black Studies Center at Reed. The BSU rolled up their sleeping bags and left Eliot Hall. They’d been there a week.

***

While everyone was on winter break, the professors on the Faculty Advisory Committee, or FAC, a 10-member body chosen from the senior faculty, fired a bunch of their younger colleagues.

ROGER PORTER: I had just gotten tenure, and I’m sure I wouldn’t have gotten tenure if I hadn’t already had it. Almost all the untenured faculty, certainly those in the humanities program, um, who had voted in favor of Black studies were let go. Between 1967 and 1971, 26 faculty members were hired into the Hum 110 program, and 25 did not get tenure, only one. So as it turned out, it was quite dangerous for the junior faculty to support the Black Studies program.

The “purge,” as it became known, prompted students to form the Student Advisory Committee, which then met with the FAC as a Committee of 8, to quote “advise the faculty on questions of student power.” Steve Engel was on the SAC:

STEVE ENGEL: Somehow or other, it came to a question of, all right, the students can elect four students to meet with four faculty. And that seemed like it was progress. It was actually a tar ball. And so they were very good at taking up the whole hour of meeting with maybe one person giving a discourse. It became clear to me, oh, these guys are vested in a way we can’t be. These guys were here when we got here. They’ll be here when we’re gone. They’re the trees and we’re just, the breeze blowing through the trees. We’re just passing through.

Over the course of the spring, as the final proposal for a Black Studies Center was hammered out, faculty votes continued to be razor thin—59 to 44 on a vote to put more people on the firing board of the FAC, 60 to 54 on the BSC proposal, etcetera. While the final proposal was ultimately accepted by the BSU in a unanimous vote, the resulting program was thin.

Faculty also continued to ignore the demands the BSU had made in the fall regarding courses about people of African descent—in a memo from April 30, the BSU urged students to boycott three proposed courses for the next year, including one called “Black Psychology,” which, like the other two courses, was proposed by a white professor. “We were not consulted as to the material and perspectives being used in these courses, and we feel that this is the epitome of white supremacy. We are discouraging all non-white peoples from taking these courses, and all white people who want a good education.”

In an interesting twist, George Brandon, who had been one of the BSU students who’d slept in Eliot Hall that week, ended up being hired by the president’s office for a summer job laying the groundwork for the new Center.

GEORGE BRANDON: In the sense we’d gone through this whole thing to get some Black Studies there and the Reed administration didn’t know anything about it. They asked me to make a summary of the structure and the nature of the courses that already existed on other colleges or universities. I felt that I was laying the structure for what would come later for whoever was going to read their report, then implement anything out of it, and also thought that maybe they would’ve asked me about what I had done, take the benefit of that. That really didn’t happen.

Reed ended up hiring as the director of Black Studies an African-American professor who was teaching part-time at the college that fall, Bill McClendon. A historian, McClendon had also been at the forefront of the civil rights movement in Portland since moving there in 1938 after graduate school. The Black Studies Center was also only allotted $30,000 total for its first year. As Calvin Freeman, the first president of the BSU, is quoted in the Reed oral history project Comrades of the Quest saying: “They didn’t invest in a Black Studies professor the way that they would invest in, say, a new economics professor, or even a new art professor. It was pretty much a slapdash recruitment. ‘Who can we get in here right away?’ Although I’m not sure how happy we would’ve been at the time with a slower process.”

MARTIN WHITE: There was the practical matter of since there was not a history of Black Studies in America … there were not teachers being trained to teach Black studies. So anybody who might be qualified to teach Black studies, there was a lot of competition. They would probably choose to go to an Ivy League school or to a historically Black university or college to teach a subject like that rather than Reed College. Reed College didn’t have a lot to attract that kind of talent.

GEORGE BRANDON: I wasn’t satisfied with the program that came out of it, and I certainly wasn’t satisfied with the director that they chose. No, it was for me, that was disappointing. That was disappointing. Of course, the other thing is there were people early on who looked at the director that was chosen and figured that he’s not going to be around that long. … but was we had nickname for him. We called him Popcorn. It was light and insubstantial.

The BSU had actually wanted Michael Harper, the poet and part-time literature professor, to be one of the co-directors of the program, along with someone else he’d recommended. Roger Porter points out some of the structural ways that the old guard undermined the new program before it even began:

ROGER PORTER: Michael Harper, who’s quite well known, um, said that he had seen the heart of darkness of the Reed faculty. What happened was that that program was quite short-lived. And it was short-lived, exactly because the faculty managed—I think it was the Educational Policies Committee—managed to withhold divisional or group credit for all the Black Studies courses. In other words, say a Black history course did not give you credit for having taken a course in the division of history and social sciences. So they were, they were in effect knee-capping the courses. And over the next couple of years, one after another of the Black students left the college and the courses died. So it was a really, an attenuation of the program completely.

GEORGE BRANDON: Those kinds of issues can persist for a long time, not just because of inertia, but also just because the right people are not there. You don’t have white students asking for Black Studies. You have Black students agitating for it.

Before President Victor Rosenblum left his post, he secured funding from a trustee for the BSC for its initial two years. But the college was running out of money. Ron Herndon reflected on this in the 1988 oral history:

RON HERNDON: They did not maintain the commitment to bring Black students. The commitment was that they had to match the Rockefeller money. Reed College never did. It was the only institution that got the money that never kept this commitment. So when the money ran out, they made no effort to replace it, nor bring in more Black students. For several years, Reed College had one Black student in the latter part of the seventies, early eighties, and now they may have seven Black students total.

And, even though the number of Black students at Reed had temporarily increased during the years of the Rockefeller scholarships, Black students were still dropping out at a worrying rate—just like they would in in the 2000s:

MARY FRANKIE MCFARLAND FORTE: It seemed like to me, most of the Black students—at least that I was friends that didn’t graduate—after two years, one year, two years, they just couldn’t take it anymore.

The peak of Black enrollment, when 35 students attended Reed from 1968 to 1970, wouldn’t be surpassed until 2007.

MARTIN WHITE: Reed was broke at the end of the sixties. There was no real endowment. They were just living from hand to mouth. And so when the Rockefeller grant ran out, they did not have special money to provide scholarships for Black students. And the student body became returned to its earlier status of being pretty white. It was kind of a death spiral, wasn’t support, there weren’t the Black students, there wasn’t funding. So eventually it just petered out.

MARY FRANKIE MCFARLAND FORTE: It says to me that maybe they didn’t really truly care. They just put something in place, a band-aid, tell us students that were involved, we kind of left. And then you don’t hear about it. They really didn’t mean it.

SUZANNE SNIVELY: I don’t think we realized just how determined they were to keep Reed on what was a more traditional vein. And it wasn’t until my 50th celebration with Frankie and others from Reed that we realized that the Black students were only there while the Rockefeller Foundation funded them. We, I guess in our minds imagined that that started a movement at Reed that would continue, and so that just shows what kind of echo chamber I was in. I was in this progressive imagination that Reed was going to grow and improve and become even better at teaching humanities.

The faculty remained pretty white, too, and pretty conservative about the curriculum—most of the more supportive younger faculty had left or been pushed out by this point. This sometimes came out in ugly ways.

ROGER PORTER: Soon after this, by a couple of years, there was an attempt or interest on the part of faculty—even though there were very few women on the faculty at that time—there was an attempt to introduce women’s studies. And while it never rose to that level of contention and mutual distrust, there was a great deal of resistance to that. And one of the prominent faculty members, who happened to be quite short in stature, in physical stature, when he was asked about the introduction of women’s studies said, “Well, what should there be next? Short men’s studies?” You know, just totally kind of grotesque misunderstanding and, you know, mocking of it.

To be fair, not all of the young faculty were radicals, and they weren’t only opposed to Black Studies:

ROGER PORTER: There was an attempt from time to time to have moratoria of classes because of a particular event, such as the shootings at Kent State, the mining of Haiphong Harbor, the bombing of Cambodia, a number of issues that were perpetrated by Kissinger and Nixon. And, uh, I think on the least four or five occasions, uh, students and faculty, uh, got together and asked for a moratorium, uh, which is to say a suspension of classes for a day to discuss issues about the war and its impact on education—obviously there were questions of drafting people in those days, and so on. And I’ll never forget, one faculty member, a young guy, um, who had been a Rhode Scholar, had graduated from Reed, uh, and came back and taught history here, I think he was no more than 25, 26, got up and said, on the floor of the faculty, one of the strangest things I’ve ever heard on the faculty floor. He said, “If I could stop the war in Vietnam, totally, by calling off my classes for even one day, I would not do it because too many other values in Western culture would go down the drain.” I’m quoting it absolutely verbatim, because I’ve never forgotten that statement. And that was not totally uncharacteristic of some faculty!

***

We’ve devoted this much time to the fight for Black Studies at Reed in 1968 not only because it was an inspiration to the students in Reedies Against Racism in 2016, but because in doing the interviews and research for this episode, the strongest feeling I had was déjà vu—and a sense of foreboding.

One of the townhalls that the BSU put on in the fall of 1968 happens to exist in a recording at the Reed College library. I remember so distinctly when I first listened to this tape because it was eerily similar to the arguments I’d heard in 2016 and 2017—and not just at Reed. This is a slightly abridged exchange between Cathy Allen and Ron Herndon:

CATHY ALLEN: Something else that I wanted to add on the importance of Black Studies for white students. Now some of you may think that that’s farfetched, but I want to know how are you going to get a full picture of how this country and the world has developed without knowing about all of the people in the world and you really haven’t gotten it … And even within America, you cannot paint a picture of how America came to be without taking into consideration slavery, without taking into consideration what Black people as well as Mexican-Americans and Indians and everybody else has donated to the culture.

RON HERNDON: It’s really strange now when you talk about any other course, a German literature, German history, old English history, there’s no problem. People don’t have to worry about, I wonder if they’re going to let me in there. I wonder if they’re going to let Black people in there. But the minute you say Black curriculum, everybody gets uptight or they’re going to let me in. How’s it going to be viewed?

CATHY ALLEN: Yeah, it’s kind of like people segregate themselves, I think.

RON HERNDON: That’s a good, you should check that out. You can learn a lot about what the word “Black” means to white people and the fear that it puts in them. That’s the first course in Black, in the Black curriculum taught tonight.

And something else Cathy Allen said reminded me of the arguments that were made about how Reed already had courses about other cultures and other canons, and that students were free to take those courses.

CATHY ALLEN: The difference there is you can escape Black Studies if you want to. You don’t have to take it, but to get through school, I have to take, pardon the expression, a lot of European crap. A lot of it.

In the fall of 1969, there was also a protest of Humanities 110—a boycott, in which the majority of entering Black freshmen refused to register. The chair of the course was an Assistant Professor of Literature named Sam McCracken. A leaked memo that he wrote to the Humanities staff clearly states his attitude toward the boycott:

While I believe the proposal at hand to be impractical in the extreme and positively undesirable were it practical, I hope you will all take the time to read it, and that we can arrange for the staff or a delegation therefrom to meet with the proposers. My own tolerance for student-generated twaddle is as low as any man’s but I believe that one of the burdens of authority is the obligation to give audience to the humble and oppressed, and that a corollary of our telling students who disrupt that they ought to have gone through channels, even when the process looks tedious and futile. Also, I suspect that as teachers we have some obligation to tell students who appear to be in the wrong just why they are in the wrong. There is finally the prudential argument that if we don’t give the proposal some serious attention, we may well hear about our dereliction later on.

Between 1976 and 2018, there was no way to major in Black or Ethnic Studies at Reed. It was only in March 2018, 50 years after the original Black Student Union protests, that the faculty approved, unanimously, the interdisciplinary Critical Race and Ethnicity Major.

CATHY ALLEN: If Black Studies is open at a university, this will attract more Black students and Black students of a high caliber to the particular college that’s offering it. On top of that, a lot of reasons why a lot of Black students don’t go to college is because they’ve gotten their full in high school of hearing all about the white power structure and why should I go on and hear more of this? If this is open to them, not only will it bring more students into college period, but it will attract more students to Reed.

And then, there’s the way that animosity amongst the faculty destroyed the Black Studies program.

A 1980s Reed report detailing the history of minority student recruitment on campus says of the 1968 takeover: “It seems to us that the wounds from this series of events are still raw. Many faculty with whom we have talked trace their antipathy to black studies courses to those events.”

Todd Schwartz ends his Reed Magazine article with a bunch of quotes from professors, some of whom didn’t even want to give their names in 2003! “This quite literally split the college in two. And the memories were painful even years later.”

By some accounts, the same thing nearly happened in the later fight over Hum 110.

****

CREDITS: I owe enormous thanks to Martin White, who spoke with me for several hours last summer and fall about his research and memories about the fight for Black Studies at Reed. His article for the Oregon Historical Quarterly, in addition to being the basis for this episode, is a goldmine. It goes into far more detail than I could and is linked in the episode notes. Stephen Robinson took all of the photographs you’ll find attached to this episode, and without him I wouldn’t have been able to connect with all of the BSU members and their allies featured here. He was also kind enough to be the voice of the BSU printed matter. Thank you to each and every one of the BSU members and their allies for digging into a painful but proud episode from more than 50 years ago: Mary Frankie McFarland Forte, Andre Wooten, George Brandon, Steve Engel, and Suzanne Sniveley. Thank you to Cheryl Woodruff and John Lonsbury for your conversation, though we weren’t able to record an interview. I could not have made this episode without you. A special thank you to Tracy Drake, the Director of Special Collections and Archives at the Reed College Library, for steering me to the incredible recording of the 1968 forum in the Student Union, and for all her assistance in the archives. Thank you to Roger Porter, one of the few unpurged Young Turks of the Reed faculty in the 1960s, for taking the time to talk to me. The Oregon Historical Society does incredible work, including the oral history with Ron Herndon sampled here.

Lastly, this episode is dedicated to the memory of Linda Gordon Howard, the first BSU member I spoke with and the founder of Reed College’s Renn Fayre celebration, who died on September 13, 2023.

Original music by the Rhae Royal. Audio storytelling consulting from Mickey Capper. Any mistakes are my own.