Travel to any of the hundred-odd countries where malaria is endemic, and the mosquito is not merely a pest: it is a killer. Factor in the laundry list of other diseases that this insect can transmit—dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya, filiaraisis, and a litany of encephalitises—and the mosquito was responsible for some 830,000 human deaths in 2018 alone. This is the lowest figure on record: for context, one estimate puts the mosquito’s death toll for all of human history at 52 billion, which accounts for almost half our human ancestors. How did such a wee little insect manage all that, and escape every attempt to thwart its deadly power? To answer that question, Timothy C. Winegard wrote The Mosquito, a book spanning human history from its origins in Africa through the present and toward the future of gene-editing. In its 496 pages and 1.6 pounds—the equivalent of 291,000 Anopheles mosquitoes—he outlines how the insect contributed to the rise and fall of Rome, the spread of Christianity, and countless wars—not to mention the conquest of South America, in which the mosquito both sparked the West African slave trade and, ironically, led to its end in the United States.

Go beyond the episode:

- Timothy C. Winegard’s The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator

- If it seems like we’re linking to Harriet A. Washington’s essay “The Well Curve” with every other episode—you’d be right! The majority of the neglected tropical diseases she identifies are borne by—you guessed it—mosquitoes.

- To help you sleep even less at night, here is the WHO’s list of mosquito-borne diseases and a 2019 report on how climate change puts billions more at risk

- We recommend listening to this episode with a citronella candle at hand—and you can consult the CDC’s guidelines for preventing mosquito bites for more tips

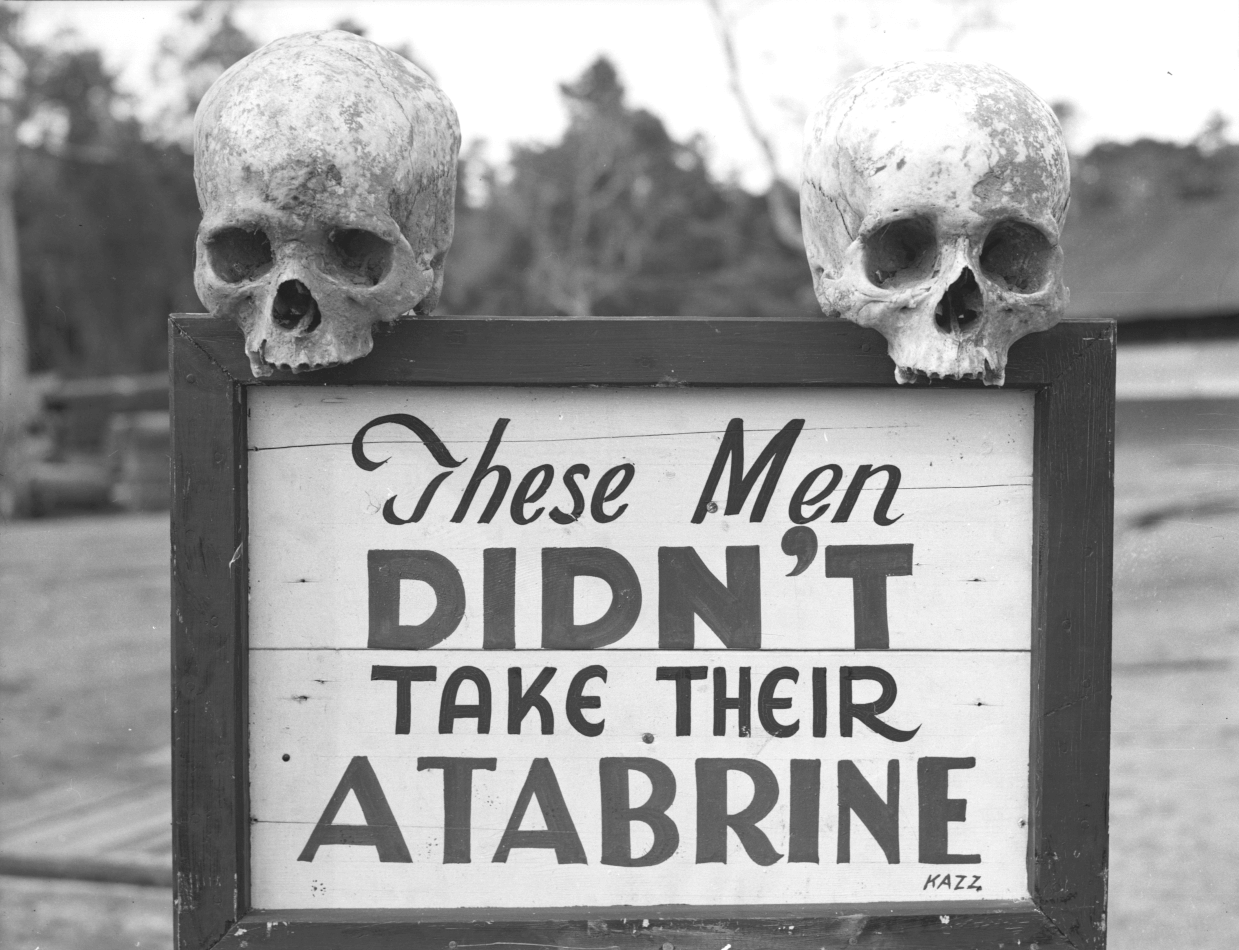

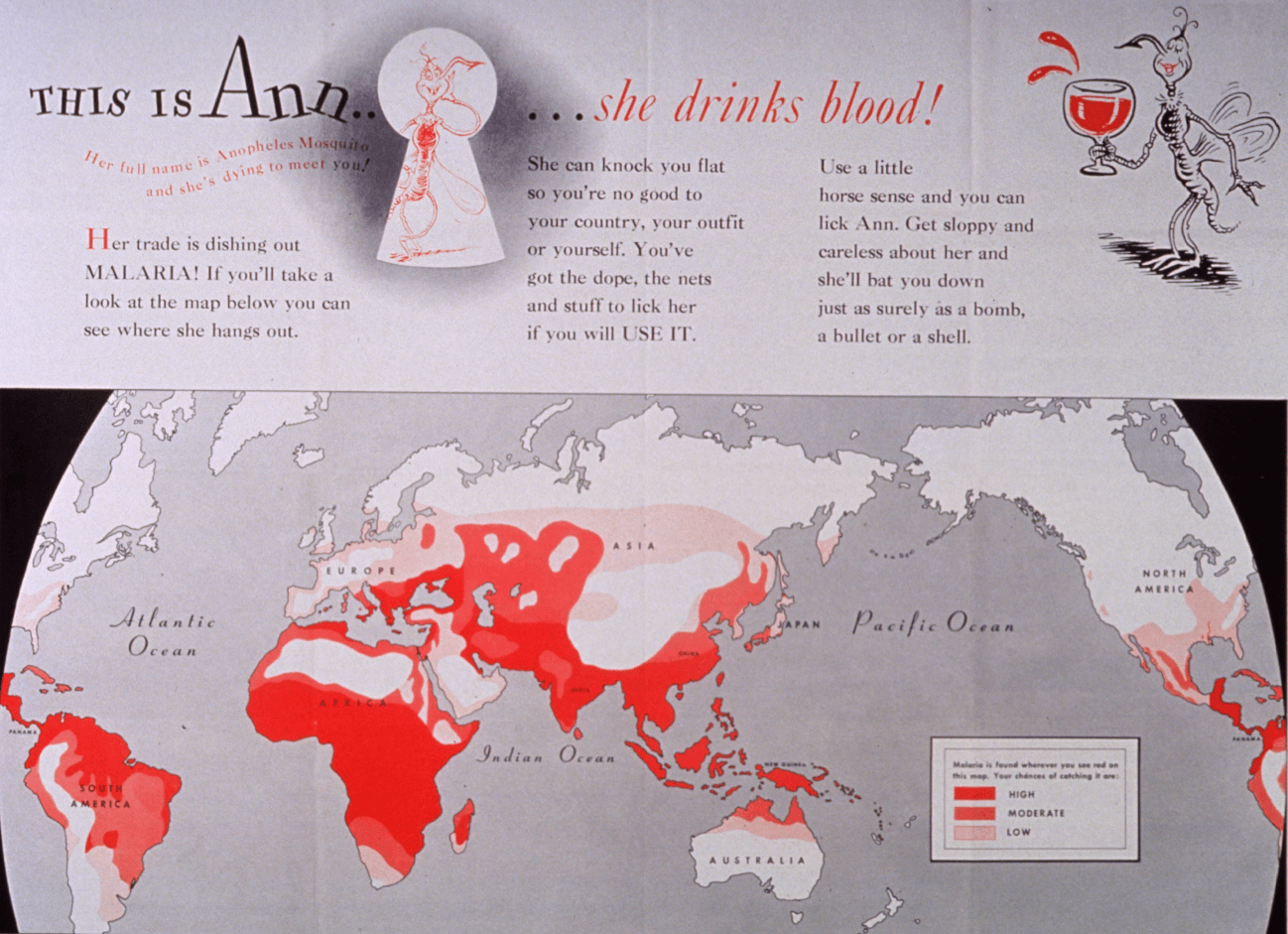

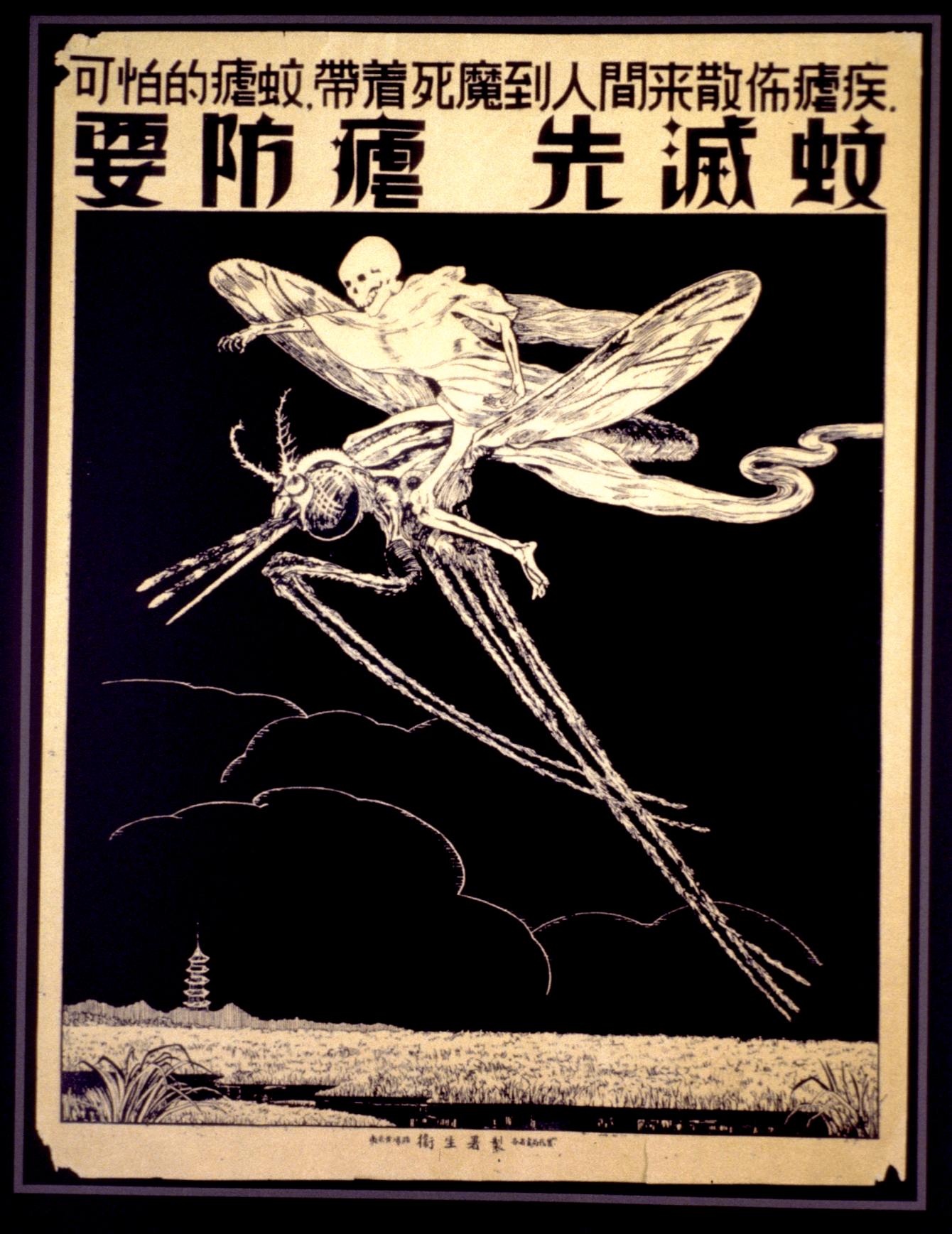

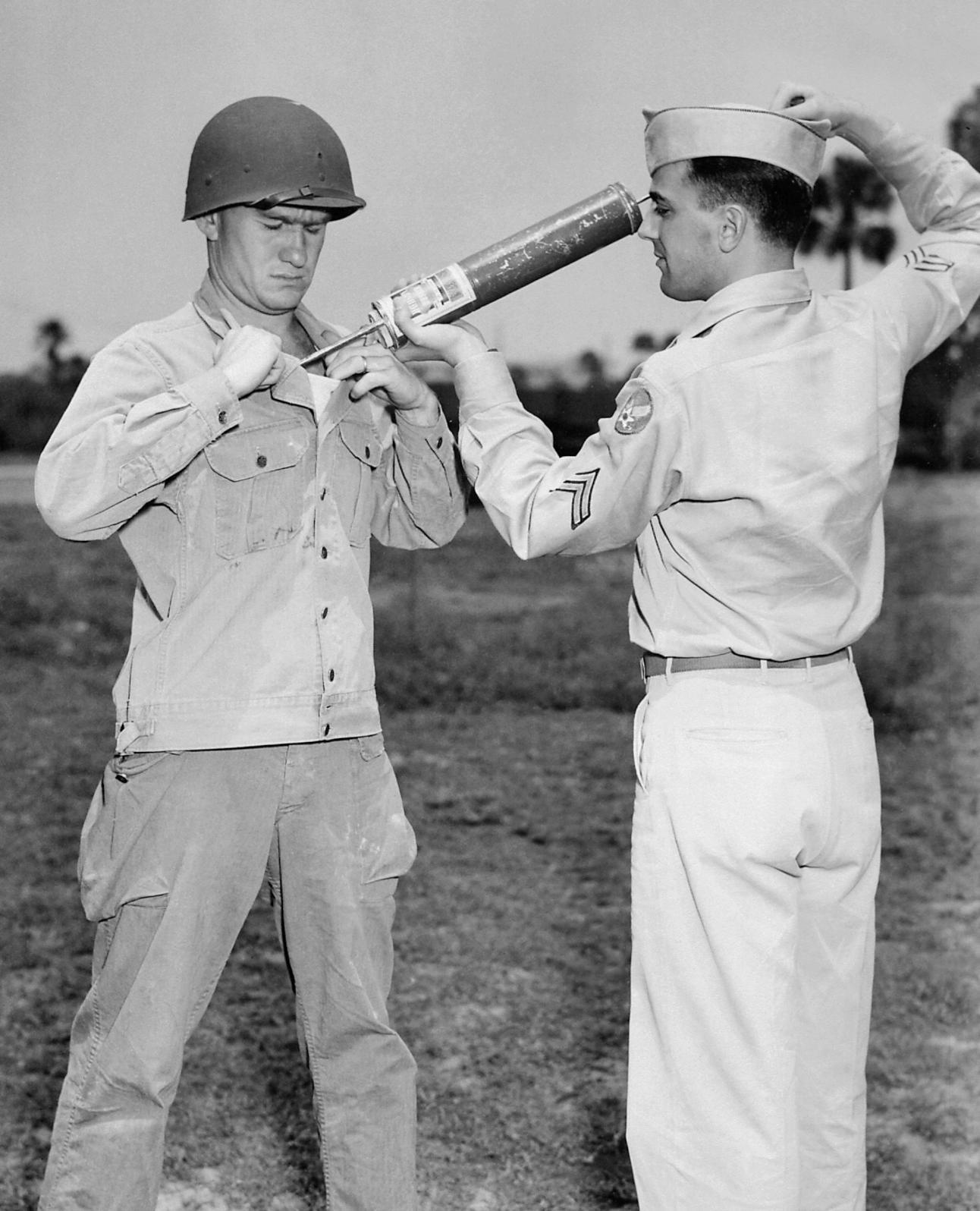

A gallery of anti-mosquito efforts, courtesy of Dutton:

Tune in every week to catch interviews with the liveliest voices from literature, the arts, sciences, history, and public affairs; reports on cutting-edge works in progress; long-form narratives; and compelling excerpts from new books. Hosted by Stephanie Bastek. Follow us on Twitter @TheAmScho or on Facebook.

Subscribe: iTunes • Feedburner • Stitcher • Google Play • Acast

Download the audio here (right click to “save link as …”)

Have suggestions for projects you’d like us to catch up on, or writers you want to hear from? Send us a note: podcast [at] theamericanscholar [dot] org. And rate us on iTunes! Our theme music was composed by Nathan Prillaman.